A Tale of Two Dominique Pamplemousses

On a bright, late April day, Squinky walked up to the third floor of a typical Plateau triplex and rang the bell. I put on a kettle and made a pot of jasmine tea. The cat came out to greet them like an old friend. Squinky took my heavily disheveled demeanour in good stride.

We drank our tea and caught each other up on what had happened in our lives since we last spoke. Squinky explained to me that the release of “Dominique Pamplemousse & Dominique Pamplemousse in Combinatorial Explosion!” coincided with their goal to fundraise for top surgery throughout the month of April.

(To help Squinky raise funds for post-op recovery expenses and to ensure the development and existence of future games, please buy their games on squinky.itch.io!)

The first “Dominique Pamplemousse” game (amusingly and intriguingly designated a “claymation noir” by Alec Meer[1]) was released in 2013, and this long-awaited sequel to the original had been in the works for a while.

After I set my computer in my living room to download both Dominique Pamplemousse games, Squinky and I decided to go to a nearby dépanneur to grab some snacks before starting our play-through. As we walked down the street, I looked up at the almost completely clear blue sky and felt quite energetic. I love the kinds of games that Squinky creates completely from scratch—which could possibly be described as “altgames,” though the term is contentious and possibly falls short to describe Squinky's highly textured and polished games—and it was a real treat that Squinky decided to take some time out of their schedule to spend the day with me as I discovered both Dominique Pamplemousses.

When we returned from the dépanneur with our bounty of snacks and soda and got ready to embark on an afternoon of musical theatre videogames, Squinky told me that they would be actually be interested in seeing my reaction if we could play the second Dominique Pamplemousse game first. As someone who had yet to play either the original or the new one I was pretty happy to acquiesce to Squinky’s curiosity, as we fired up “Dominique Pamplemousse & Dominique Pamplemousse in Combinatorial Explosion!”

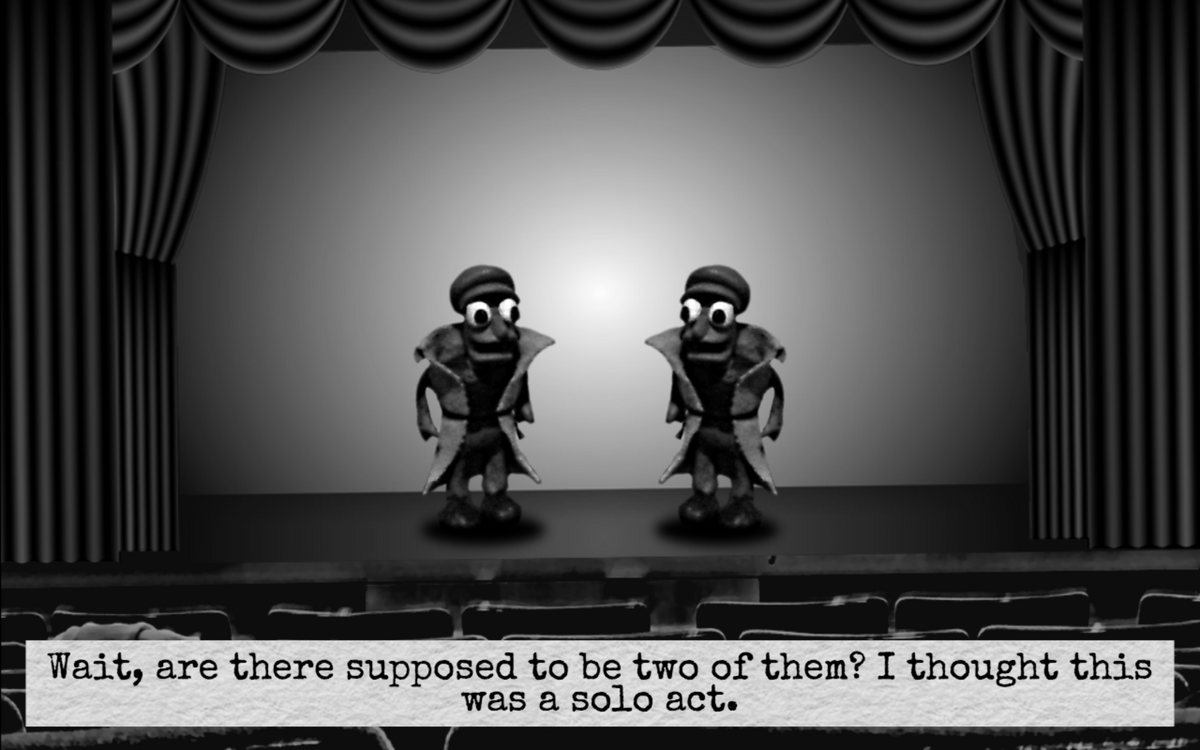

“Dominique Pamplemousse & Dominique Pamplemousse in Combinatorial Explosion!” is an odd, whimsical, but utterly charming game. It is a one-person piece of musical performance art which accepts audience participation and input. Every bit of voice acting, song, and musical instrument playing is performed and recorded by Squinky themselves, and the end result is a hilarious tapestry which during its most effective moments, questions and parodies at least a half-dozen videogame/altgame genres, makes fun with selfhood and identity, and also addresses questions of authorship and the author's presence in their work. Weaved into the narrative and in most scenes are all the cloned Dominique Pamplemousse’s (delightfully meta) running commentary on the game itself,

millennials, contending with the cis gaze, videogames as a cultural (and creative) artefacts, and interestingly, about finding love in the most unlikely hellish landscapes.

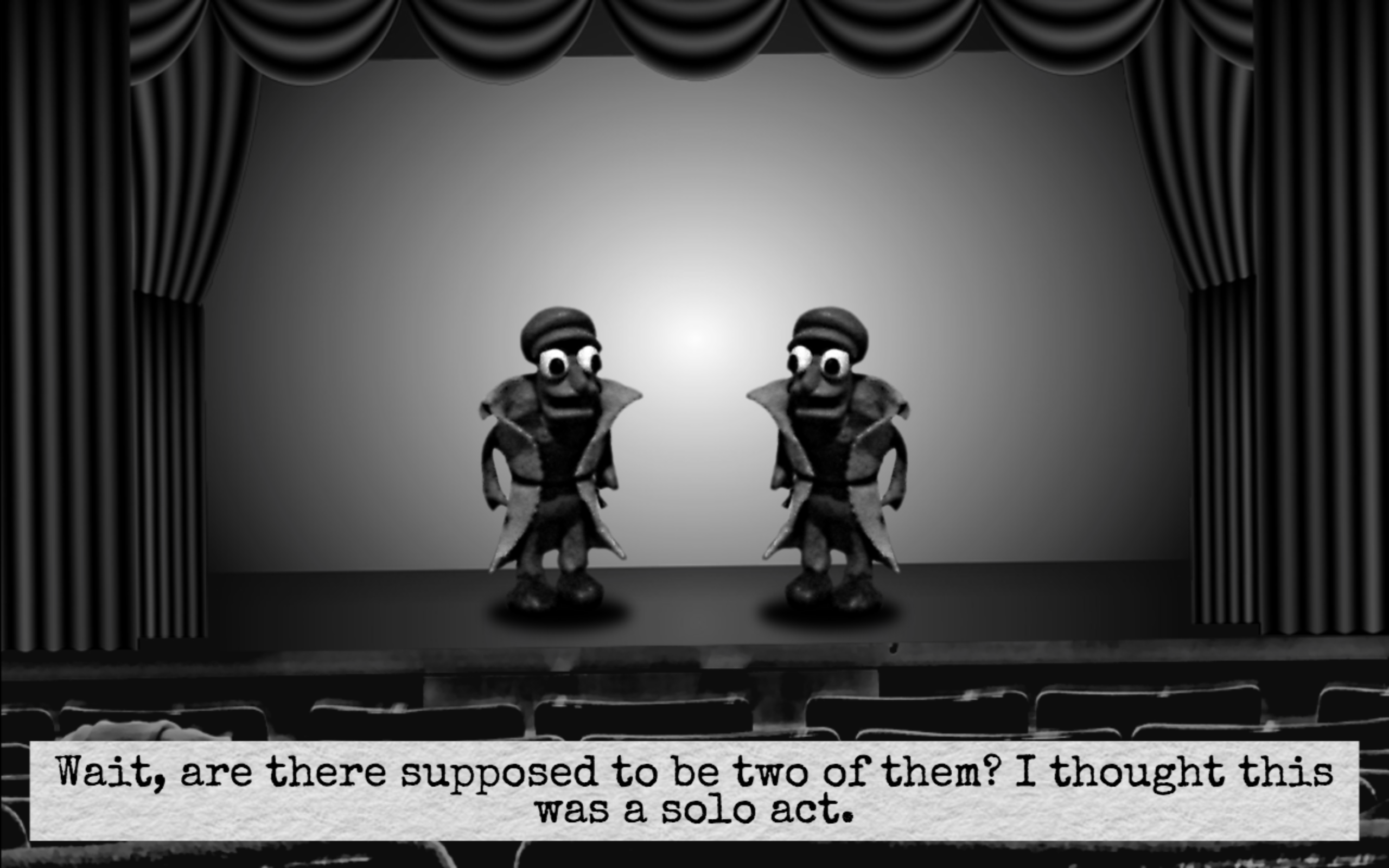

In their opening duet, Dominique Pamplemousse and Dominique Pamplemousse both arrive somewhere: a grey and white alleyway dotted with dumpsters. It’s the exact sort of in-between place where you would expect to experience a glitch in the narrative time/space continuum: those decaying places that lead everywhere and are nowhere. Dominique Pamplemousse has been metaphorically "thrown away" into these back alleys since the last game—regardless of which ending was chosen.

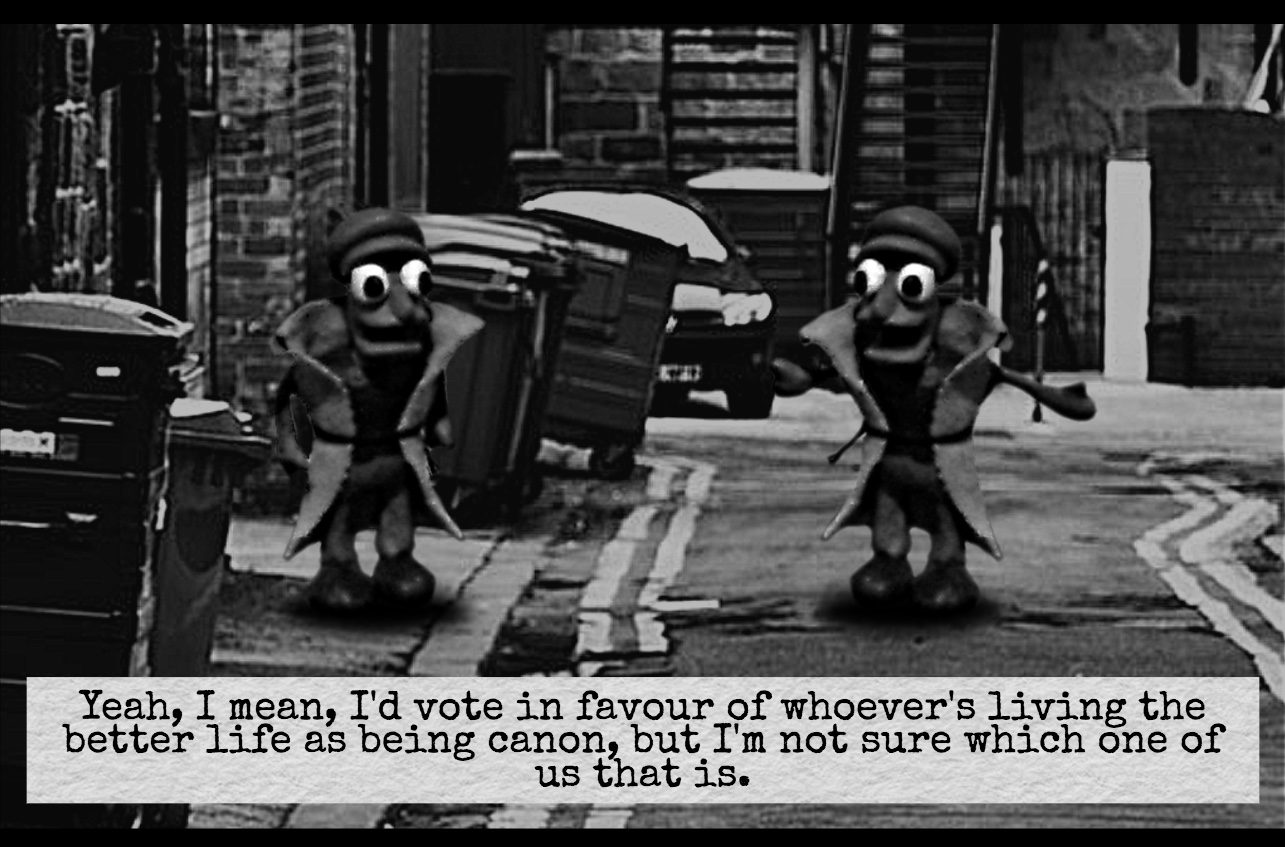

Immediately, one Dominique Pamplemousse realises there is an other Dominique Pamplemousse present—a clone, perhaps, created somehow by the fact that both the endings of the original Dominique Pamplemousse game came true. What Dominique Pamplemousse and Dominique Pamplemousse want to know is which one of them is the real deal—the canon Dominique Pamplemousse, so to speak. Each Dominique’s dissatisfaction with their choices and life lead them to conclude that none of the “endings” felt real, as they both ascribe to the idea that an ending, even if not a fairytale happy one, should at least lead to some kind of better life. As they each admit in their song: “I chose wrong.” The question becomes the driving force of the second game otherwise divorced from the mechanics and storytelling style of its previous iteration: which one of the two endings of the first Dominique Pamplemousse game was the real ending? Which one of the Dominique Pamplemousse…s is real?

To its credit the game doesn’t worry much about things like a coherent setting linking together each one of its scenes, or how this universe’s geography and landscape fits in with the original game’s. Instead, each scene is much like a stage, delineated on four sides by the end of that stage (sometimes the Dominique exit left, sometimes right). The game doesn’t much care to explain what links theses stages, or how the Dominique Pamplemousses are able to transition so seamlessly between videogame genres and different stages. Combined with the expository singing, the game feel very much like performance art.

Musical theatre and music in the theatre, as I’ve always understood it, is distinguished by the answer to the question: “Do the characters know that they are singing?” For example, in one of the more famous scene of Pedro Almodóvar’s film Volver, the main character (played by Penélope Cruz and her singing voiced by Estrella Morente), her family and her neighbours gather together to watch Penélope’s character sing to accompany flamenco guitarists. The performance and song becomes the soundtrack (and a crucial storytelling and dramatic peak) of the film, but because all the characters in the scene know that they are singing or playing guitars or listening to a performance, that scene from Volver would not be considered an example of “musical theatre” in a film. The key difference between music performed in theatre, film, and even games versus the genre of musical theatre is that the characters in a musical, even when switching between regular dialogue and song, do not necessarily know that they are singing. Your mileage may vary, as there are of course many interesting exceptions and subversions to this, an example being the Buffy The Vampire Slayer episode “Once More With Feeling.”

So does the second Dominique Pamplemousse game count as musical theatre? It certainly flirts quite a bit with the style, but in its usual fourth-wall breaking manner, the game seems to channel the musical theatre genre when its useful, and then often outright lampshades it for hilarity’s sake. Doing so gives the game enough space to mess and play with otherwise clearly delineated boundaries between author, story and audience.

In some ways, this Dominique Pamplemousse sequel reminds me a little of the manner in which some transformative works behave, especially in its playfulness and the manner in which the main character(s) of the game react to the differing, constantly changing scenes (and sometimes genres). Squinky uses the possibilities behind each stage and setting in order to critique or make fun with/of a different subject or theme, in a manner that is coherent with the Dominiques’ main quest of figuring out the author’s “true” intentions.

Though “Dominique Pamplemousse & Dominique Pamplemousse in Combinatorial Explosion!” reminds me much more of transformative work, in this case the transformation is created by the original author, themselves playing with their own canon and creations. During my play-through of the first game, Squinky was usually observing quietly, but they shared with me an intriguing detail when I arrived to the one particular scene which most directly deals with the events and characters from the first game. In the scene, when you encounter the ghost of a murder victim from the previous game, the music that plays in the background is actually a fan-made remix of one of the songs from the first game!

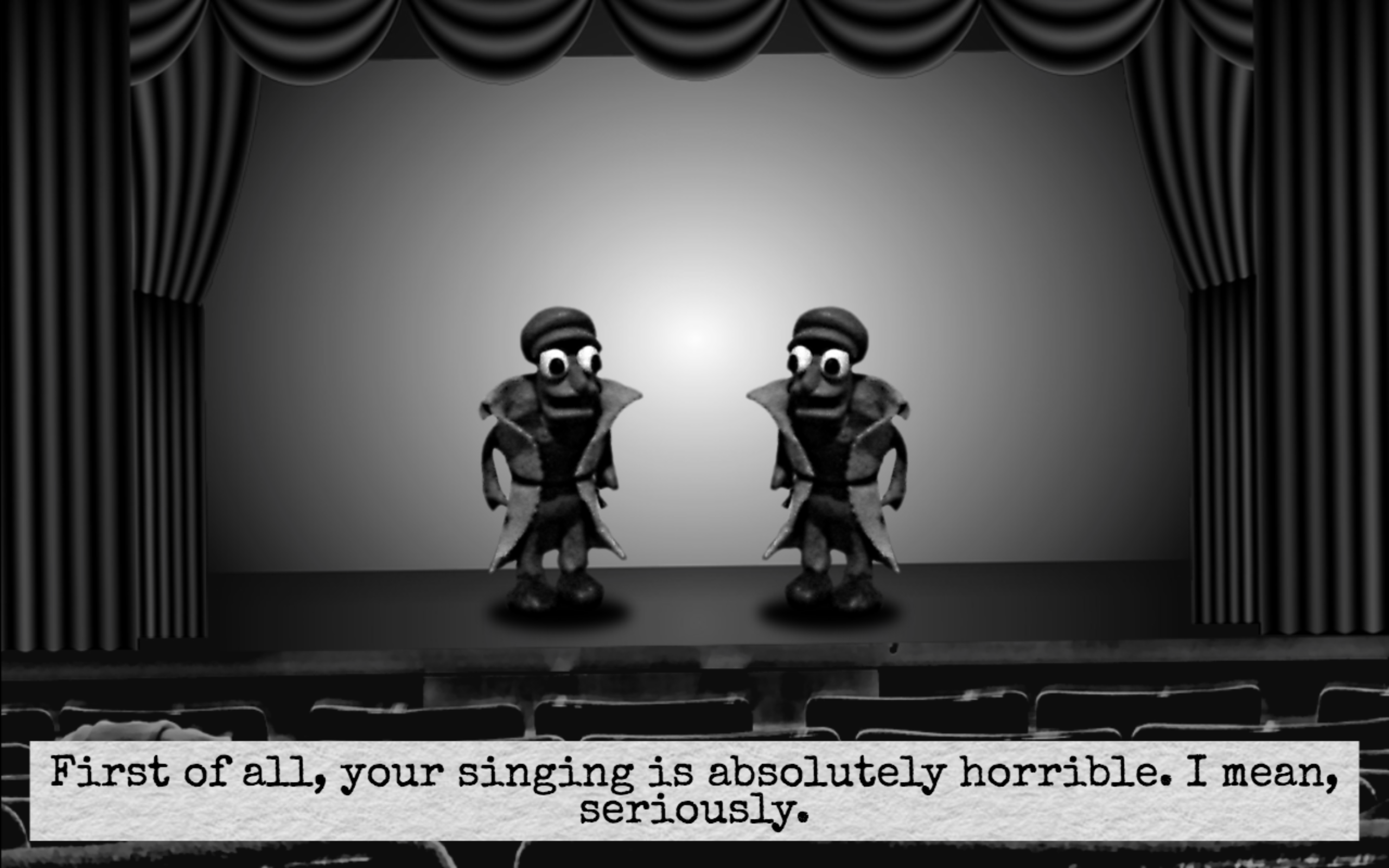

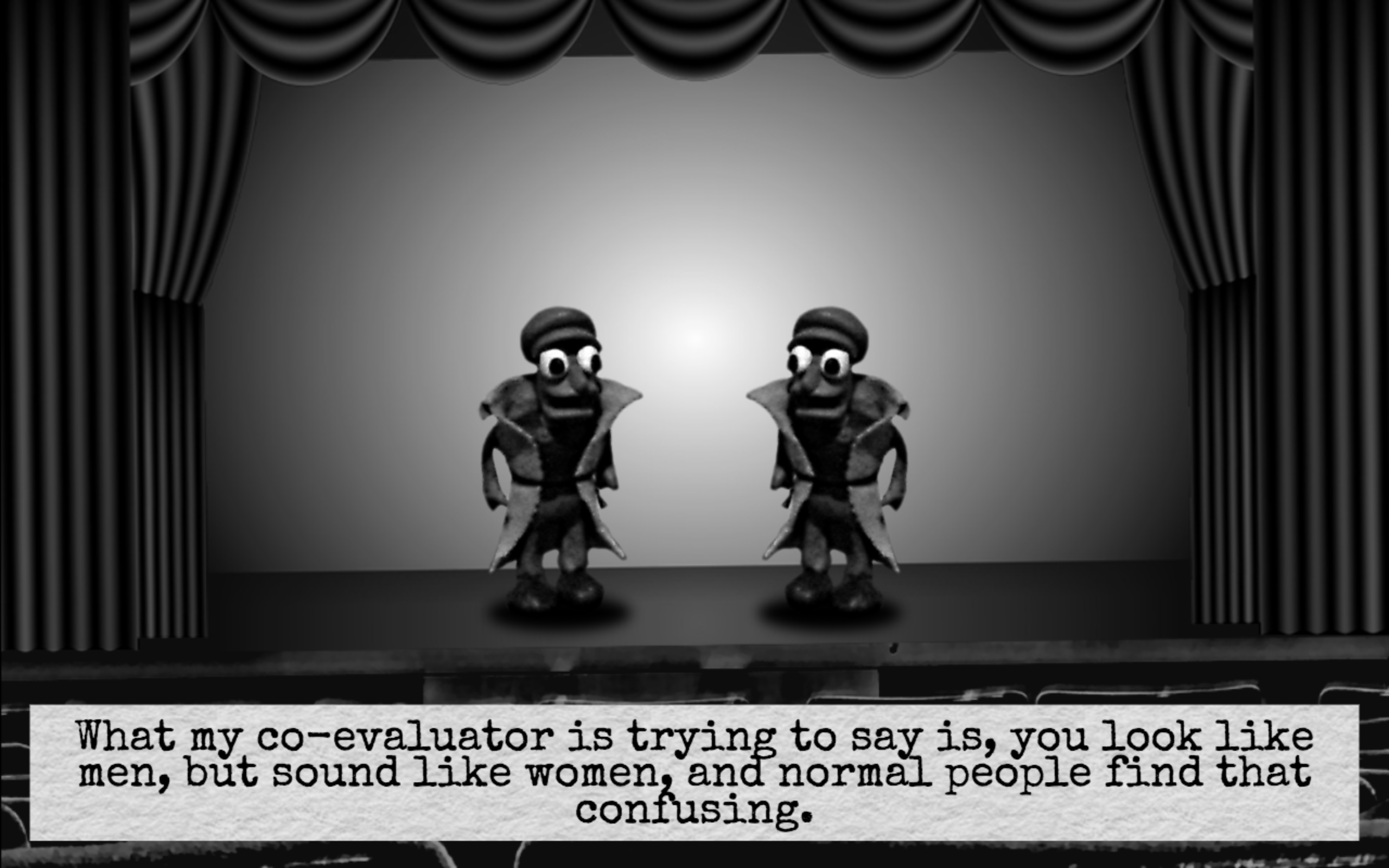

The game reacts to its perceived, intended audience in another meta-sense by directly contending with the cis gaze in one crucial scene. And by cis, I mean cisgender. Through the characters Dominique Pamplemousse and Dominique Pamplemousse, Squinky is able to look right back into that cis gaze and comment on it, even respond to it. In an early scene of the game, both Dominique Pamplemousses stand upon a stage where they are waiting to be judged by two disembodied voices in the audience—and I don’t think it is a mistake that one disembodied voice could be interpreted as coded female, and the other disembodied voice could be interpreted as coded male.[2] These disembodied judges briefly channel the binarist (“adhering strictly to the female-male gender binary”), cis gaze judging the entire game—and by extension, its author.

The judge exclaims, reacting to both Dominiques: “What my co-evaluator is trying to say is, you look like men, but sound like women, and normal people find that confusing.”

On top of the myriad of issues that transgender people face, the Dominique Pamplemousse characters give the game the opportunity to elaborate on nonbinary transgender people and their particular experiences with the cis gaze. A very common barrier nonbinary people face is that people just don’t know how to react to nonbinary people. The issue goes beyond representation in that we live in such a rigid, cisgender world that it’s not uncommon to find people who, even if they can eventually come around to the idea of people “transitioning”[3] from one side of the binary to the other, they simply do not know how to react to people who purposefully do not conform to the gender binary. The cis gaze is well-documented to be obsessed with transitioning, surgeries, inappropriate and invasive queries about genitals and hormones, as well as misunderstood scientific ideas, sometimes known as “biological essentialism.”

As described in Dominique Pamplemousse, another one of the primary behaviours of the cis gaze is to willfully or carelessly ignore and deny transgender people. As the judges in the game tell Dominique and Dominique, “normal people” (in this case, cisgender people) find transgender people confusing, so they will refuse to make any extra effort to tolerate or accept them. The cis gaze is only curious when being curious means it will be able to reassert cisgender superiority. In another line of dialogue, one of the judges even jokes that the only way they would find the Dominiques acceptable is after they’ve had “a lot of cosmetic surgery.” It is a common societal requirement for transgender people to undergo cosmetic beyond other kinds of invasive sexual reassignment surgeries, otherwise their families, social circles, and strangers will refuse to interact with them in a manner appropriate to the gender that they are.

With regard to nonbinary people, there is another layer of meaning to be found in the judges’ cosmetic surgery insult, highlighted when the judges say: “(…) androgyny is in right now. That said, you have to have a particular body type to pull it off, which you very much emphatically lack.” Androgyny is sometimes accepted by the cis gaze—one of the most famous examples could be found on the 1970s haute-couture fashion runway, as pioneer Grace Jones modelled for Yves Saint Laurent, inspired countless designers and trends and even appeared on the cover of Vogue and other mainstream magazines. But as the judges tell Dominique Pamplemousse fois deux, to successfully be interpreted, accepted, and celebrated as androgynous, you usually have to conform to a narrow slice of gender non-conformity. You need to be considered highly desirable and attractive, usually fair or white, well-dressed and, most importantly, skinny. This kind of performance of androgyny usually fails to threaten the cis gaze, as it accepts the performance as just rebellious enough to be interesting to look at (“eye-candy”) without threatening the cisgender paradigm.

So here comes Dominique Pamplemousse (fois deux) in their frumpy clothes, on a stage to be judged by the cis gaze, and they fail to measure up to the acceptable standards of gender non-conformity as set out by the cisgender paradigm. As one of the judge says: “For starters, how do you think anyone is going to take you seriously with your oddly-shaped, bug-eyed faces and shabby clothes?”

And this is a common problem for nonbinary people. Is the use of “they” pronouns (and other gender-non-conforming pronouns) a serious enough cause for transgender activists to get behind and get agitated about? Is it at all acceptable to ask not to be described using gendered terms, or do you seem childish, immature, or whiny for asking for that courtesy? Are we even serious about our gender identity, if we don’t conform to sensationalized, medicalized, pathologized expectations about how transgender people are supposed to be? Isn’t it just the latest fad to use singular they pronouns?

Are we serious enough for the real world?

Are we real enough?

Dominique Pamplemousse 1: I mean, we get that you have a right to your opinion, but you don’t have to be abusive about it.

Judge 1: You see, that’s the problem with you millennials: you always demand to be coddled.

Judge 2: It’s about time you learned to live in the real world, where, I must reiterate, there are no trigger warnings.

Dominique Pamplemousse 2: (…) Have you, by any chance, written an online think piece lately?

Dominique Pamplemousse 1: (…) Are you thinking what I’m thinking, Other Dom?

Dominique Pamplemousse 2: Happy Birthday on three?

What can you do when the cis gaze refuses to change its expectation with you? Make people uncomfortable, I guess, and then exit stage right. But it’s a serious question that the game often returns to. Contending with being nonbinary (“neither monsieur’s nor mademoiselles,” as another character puts it in another scene) is a particular set of challenges that the Dominique Pamplemousses must face again and again, often coping or responding by using some sardonic singing. There are also moments where the two main characters admit their own confusion concerning gender neutral language, such as in the twine parody scene, when they admit the use of singular they pronouns can be confusing in texts.

In a videogame often reacting to gender binaries, there is another kind of binary referenced. If Dominique Pamplemousse and Dominique Pamplemousse represent an “other” gender inaccessible to the binaries of the cis gaze, then the game itself doesn’t really fall into either of two categories of videogames. One category is the hyper-violent, usually arbitrarily patriotic, massively commercial first person shooters, and the other category is the independently-made, much cheaper to produce personal interactive fiction game that’s gotten a huge boost in the last half-decade through the rise of tools such as twine. The two Dominique Pamplemousses complain about both scenes that parodies FPS (first person shooters) and twine games. In the case of the FPS parody, the three-dimensional movement, confusing and senseless violence and ever-changing screen gives them motion sickness. In the case of the twine games parody, the dripping sound embedded in the background of the game is annoying, and the Dominique Pamplemousses agree that the sound seems unnecessary even if it was what the author intended.

I juxtapose these two scenes particularly because I find they have interesting implications. They are two scenes that drastically differ in presentation from the rest, and both scenes do not contain dialogue with another "person" but instead both Dominique Pamplemousses are instead playing a game within a game.

As I later discovered while playing the original Dominique Pamplemousse game, the first game’s mechanic was largely similar to the “point and click” mechanic of videogames such as Myst or Riven. The second game does not rely on players interacting with a clickable scene or background, rather, you press a button to advance the dialogue and occasionally can chose the order in which Dominique Pamplemousse can ask a question to someone else. In a sense, by losing the "interactive" feel of the first game, the second Dominique Pamplemousse game has much more in common with text-based videogames. Yet the scene where the two Dominique Pamplemousses play the twine game is quite funny, as their running commentary often mirrors common complaints and remarks I’ve heard over the years regarding twine games. The game treads lightly, however, while poking fun at personal twine games and their sometimes incredible randomness. This is not an accident, as Squinky has also created many twine games over the years, a genre of altgames much loved by the transgender game-making community for expressing their own narratives and stories.

The dialogue in the game is one of its strongest points. What is probably the most memorable part of the genre-bending experience of playing “Dominique Pamplemousse & Dominique Pamplemousse in Combinatorial Explosion!” is that playing the game feels a little like participating in or hearing a conversation with Squinky, and getting to know what’s been preoccupying them since the first game was released. The game is a patchwork of genres and textures and textuality, and every scene sheds a little more light on the kinds of conversations Squinky has had over the years with players, friends, other game-makers, and even with themselves.

When I finished playing the second Dominique Pamplemousse game in Squinky’s company, we decided to go out to the park to enjoy the last of the evening sun and stretch our legs a bit. On our way there, we spoke a little bit about what went into creating the game, and the some of the difference between the first game and this one.

Technically, Squinky is an extremely proficient programmer and musician. Upon seeing the animated claymation figure of Dominique Pamplemousse in motion for the first time, I asked Squinky if they had made those little clay animations themselves (the answer is yes). As mentioned earlier, all the music, singing, and voice acting was done by Squinky—with the single exception of that one fan-remix from a song from the first game, though the remix was of Squinky’s own music. The first Dominique Pamplemousse game was created using Flash (ActionScript), but this second game was written using Javascript. They described to me the process of programming in the audio dialogue and song, so that it would always match the beat and tempo of the background music in each scene.

With pride, they said that they had now reached a point in their path as a programmer that they had written enough custom libraries and templates that whenever they needed to implement a particular game mechanic, they usually had their own custom code to rely and tinker with. As they shared with me, that comes in very handy during game jams!

As we crossed the park, Squinky told me a little bit about their experiences with the first Dominique Pamplemousse game, and the experience of having a game “make it” in the indie scene. It was selected for the Indiecade 2013 E3 showcase and won several nominations in 2014, and for a quirky game produced by one person, it got pretty far. Squinky admitted to me that their expectations for the second game have been tempered by their subsequent experiences in the videogame community in the four years since, but that they were looking forward to seeing how the game would be received.

By their own admittance, Squinky’s changed a lot since the first Dominique Pamplemousse game went out into the world. This second game retains a lot of what was excellent from the first: adorable music and songs, endearingly miserable characters and the ability to poke fun at itself and anything. There was also in the first game a subtle but present political sensibility that has matured and developed in the second game, and that sensibility was often pointed both inwards and outwards. There may not have been a happy ending after the first Dominique Pamplemousse game, but there's a distinct sentiment of hope, and resilience, in the second Dominique Pamplemousse, that makes one think that if we've survived so far, we'll probably survive whatever else gets thrown our way.

During our walk, Squinky looked like they had found that elusive feeling of being comfortable in one's own skin. They radiated self-assurance and calm. We both sat for a while in the cool April evening, watching the sunset.

Notes

“[Squinky]’s down-on-their-luck gumshoe use-thingy-on-thingy game is endearingly ramshackle, and while my time with the demo suggests meaty puzzles perhaps aren’t in great supply, this is all about the plasticine and monochrome look. And the sudden outbreaks of exposition via Moldy Peaches-esque song.” (Rock, Paper, Shotgun, April 2nd, 2013) ↩︎

I use the word “coded” here purposefully and meaningfully. We subconsciously imbue meaning and exhibit bias in interpreting our senses, and I want to problematise the knee-jerk, binarist (as in: “adhering strictly to the female-male gender binary”) reaction that a high-pitched voice is immediately described as a female voice, and a low-pitch voice would be immediately described as a male voice. ↩︎

As transgender actress and activist Laverne Cox says on the cultural obsession with gender reassignment surgery and the medicalization of transgender narratives: “The preoccupation with transition and with surgery objectifies trans people.” (source) In another interview, Laverne has also said: “We are born as who we are. The gender thing is something that is imposed on you.” (source) The dominant narrative around transgender issues is a narrative obsessed with surgeries. The media frenzy surrounding the surgeries (real or imagined, cosmetic and otherwise) that Laverne Cox has received since her rise to fame as a transgender actor has been astounding to behold, and reveals the true intentions of the cis gaze. ↩︎

As transgender actress and activist Laverne Cox says on the cultural obsession with gender reassignment surgery and the medicalization of transgender narratives: “The preoccupation with transition and with surgery objectifies trans people.” (source) In another interview, Laverne has also said: “We are born as who we are. The gender thing is something that is imposed on you.” (source) The dominant narrative around transgender issues is a narrative obsessed with surgeries. The media frenzy surrounding the surgeries (real or imagined, cosmetic and otherwise) that Laverne Cox has received since her rise to fame as a transgender actor has been astounding to behold, and reveals the true intentions of the cis gaze. ↩︎