Reading Notes on Fourteen Wolves: A Rewilding Story

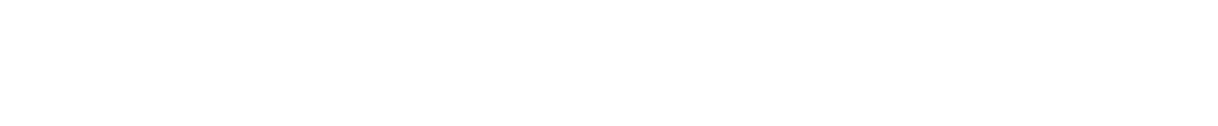

A graphic novel caught my eye recently, the French translation of Fourteen Wolves: A Rewilding Story by Catherine Barr and Jenni Desmond.

A few weeks ago, I decided to stop by the Port de Tête bookstore to check out their bandes dessinées. One graphic novel caught my eye, the French translation of Fourteen Wolves: A Rewilding Story by Catherine Barr and Jenni Desmond.

I think I was looking for something to cheer me up, and this graphic novel was so very tempting! The volume is separated into three parts: the first section sets the scene in the winter of 1995, before the return of the wolves, who by that point had long been hunted to extinction in Yellowstone. It is not specified that it was the settlers, i.e. the Americans — and not the indigenous people — who killed all the wolves. This lack of awareness on the colonial realities of the situation reflects the graphic novel's origins, as it was originally released in Britain and translated in Paris.

In the absence of wolves, the elk (the translation may be French, but I appreciated the use of the Quebec word wapiti here since it is a distinct species) have multiplied to form herds in the tens of thousands of individuals and, without predators, the environmental impact of these huge herds is apocalyptic.

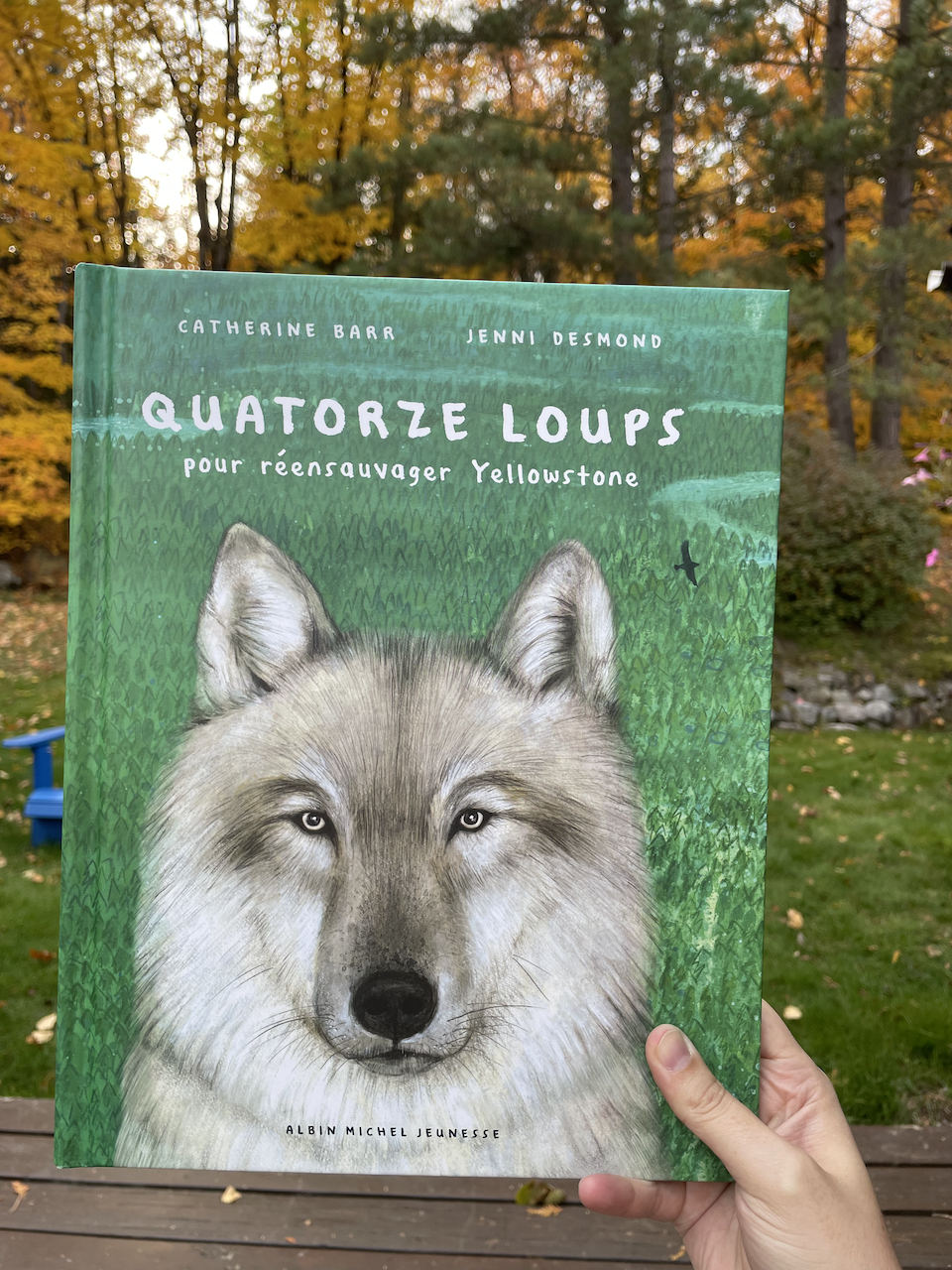

Photos of the cover and opening pages of the graphic novel, featuring the two kinds of artistic styles used in the novel.

These first fourteen wolves come from the Canadian Rockies. On a snowy night in the middle of winter, the fourteen are captured and brought into Wyoming, the first wolves to set foot in Yellowstone in over seventy years.

The obstacles to reintroduction are many; humans remain a serious threat. Hunters and ranchers in the vicinity are just waiting for the chance to kill them. Despite the hardships caused by the relocation, the wolves slowly rediscover Yellowstone. Three packs form: the Rose Creek pack, the Crystal Creek pack, and the Soda Hill pack. The first part of the comic describes their first winter in Yellowstone, how the packs begin to hunt the very unsupecting herds of elk, and, later in early spring, the first litters of cubs!

But the most fascinating part of the book is the second section, which describes the incredible beneficial effect of wolves on the Yellowstone ecosystem. Despite the graphic novel's occasional stumbles (lack of colonial awareness, the use of "alpha" terminology), it is this second section that will stay with me and, for me, ensures that it's worth the read. Through beautifully illustrated pages, the consequences of the reintroduction of wolves in Yellowstone are explored, including:

- Large trees (willows, aspens, cottonwoods, Virgina poplars, etc.) can grow in peace now that the huge elk herds are no longer destroying all their shrubs, especially along the rivers;

- Countless small migratory birds are returning to live in these trees;

- Because of the presence of large trees, beavers have returned, and their dams created shelter to fish and amphibians;

- Rivers have changed shape, flow straighter and are deeper, anchored by the large trees that prevent bank erosion.

Fourteen Wolves does a pretty good job of illustrating how an ecosystem can be reinvigorated as well as the primordial importance of predators. When I was a kid, I was fascinated by wolves — I've probably seen the movie Balto at least ten thousand times — but even more important than wolves is how the land heals thanks to their presence.

To illustrate the majesty of the Virginia poplars, I went to take a picture of my favorite specimen in Montreal, this absolutely gigantic tree in the heart of Lafontaine Park:

I've never had the chance to visit Yellowstone, Wyoming, but being able to imagine a river lined with these beautiful trees, bringing the whole land back to life thanks to the reintroduction of wolves put a very, very big smile on my face.

Read further:

- New parks podcast shares Indigenous voices: « A citizen of the Crow Nation, Shane Doyle’s ancestors were forcibly removed from the land that was eventually established as the world’s first national park in 1872. » on Indian Country Today

- Nous sommes toujours là : parcs nationaux, dépossession coloniale et résilience autochtone: « En 1885, mes ancêtres, ainsi que tous les autres peuples Niitsitapi et Îyâhe Nakoda, furent arrachés de leur territoire traditionnel (celui qui porte maintenant le nom de l’Alberta) afin de permettre la création du parc national Banff. D’abord baptisé Banff Hot Spring Reserve, puis Rocky Mountain Park, le parc de Banff fut le tout premier parc national du Canada. » on HistoireEngagée.ca (in French)

- Decolonizing The National Park System: A Story About Yellowstone, a webcomic on the colonial history of American National Parks

- Idiotismes animaliers: Les meutes de loups n’ont pas de chef by Nic Ulmi in le Devoir (in French)

- Why everything you know about wolf packs is wrong by Lauren Davis for Gizmodo

- Les loups rouges vont-ils bientôt disparaître? by Erik Vance for National Geographic (in French)