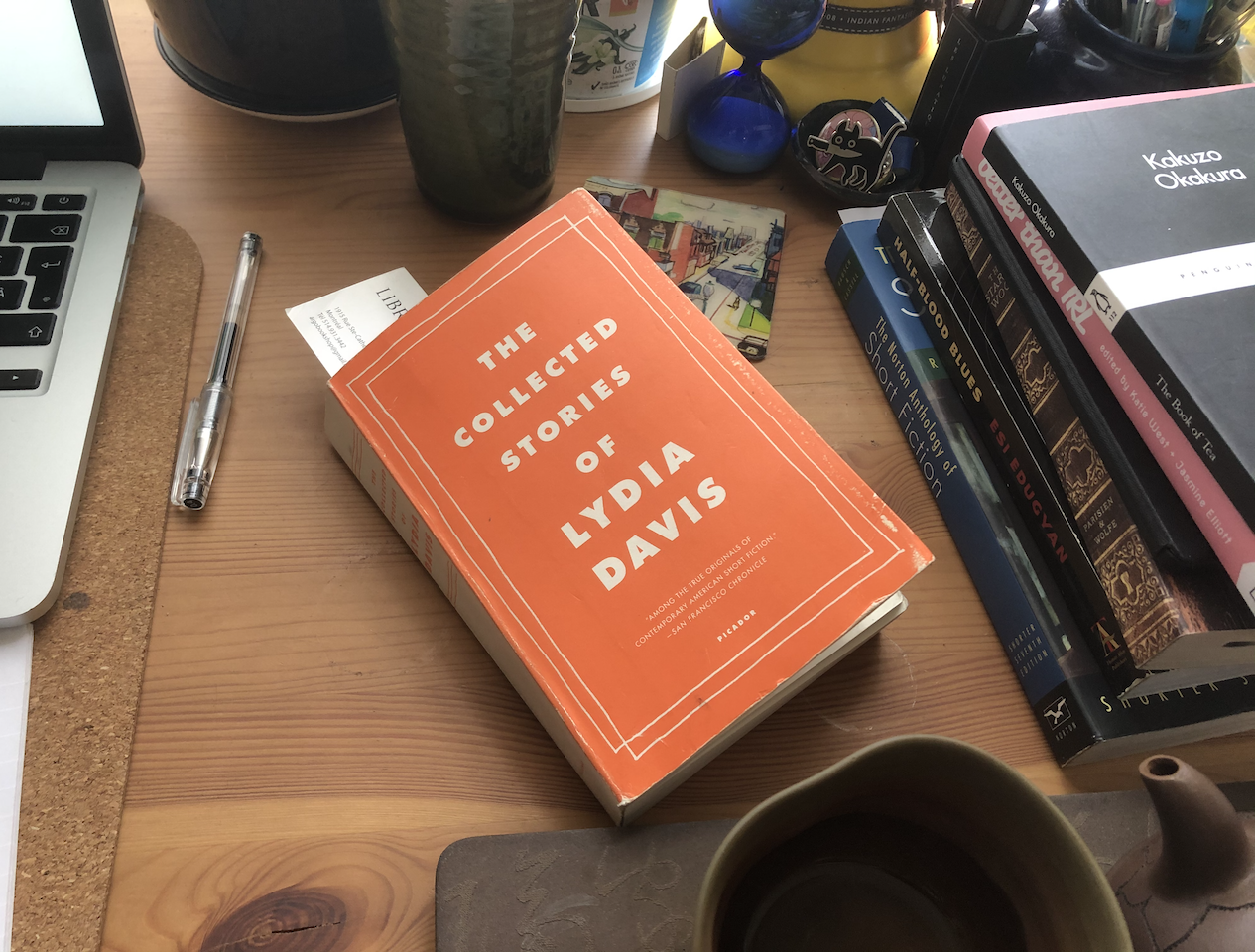

Reading Log on Cockroaches In Autumn by Lydia Davis

There is one particular short story in The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis that I’ve adored since the very first time I read it, called Cockroaches in Autumn.

There is one particular short story in The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis that I’ve adored since the very first time I read it, called Cockroaches in Autumn. It achieves this incredible balance of brevity and fullness, of admiration and disgust. There’s a kind of otherworldly quality to the narration that feels perfectly omniscient and yet first-person-limited at the same time. The story is painting the “nimble rascals”, the cockroaches, as heroic, and their infestations as somehow valiant.

There are three scenes: a beginning (the discovery of hints of cockroaches throughout the apartment); the middle (the confrontation with the cockroach); the end (the realization that the traps failed and the war with the cockroaches will never end as cockroaches are indestructible). Because of its brevity, I think Cockroaches in Autumn successfully blurs the line between poem and prose in a cool way. Every line feels imagistic and lyrical yet it conserves that short story structure (beginning, middle, end). While poems can most definitively have first-person perspectives, the narration feels expansive and crammed with history in a way that feels more typical of prose.

I keep running back and forth on what my favourite line is — and there are so many good candidates — but the line that gave me the most shivers when I first read this story remains a strong contender: “and in the crack at the top of a door, where by flashlight you see the forest of moving legs. I still think about it every time I have to open up the back panels of the shelf under the sink and reach in to shut off the hot water valve, and my hand moves into that darkness within the walls, where I know mice and all sorts of crawlies are running free and happy.

But I want to bring your attention especially to that last paragraph, which I reproduce here:

The white autumn light in the afternoon. They sleep behind a child’s drawings on the kitchen wall. I tap each piece of paper and they burst out from the edges of pictures that are already filled with shooting stars, missiles, machine guns, land mines…

The really brutal imagery (literally imagery, as these are pictures on a wall) of war interrupts these incredibly quiet scenes and leaves us with the knowledge that the resilient, unkillable cockroach is still there (“…”), so even if the story ends just like that, after three incredibly short pages, there is a cyclical, endless feeling, like we’ve just glimpsed a timeless snapshot, and everytime I reread the story, I wonder at how Davis has been able to blend domestic scenes, war imagery, and pastoral landscapes into such a tiny, compact, three page piece.