Revisiting the Introductions of When Species Meet

Donna Haraway's When Species Meet (2008, University of Minnesota Press) is a text that has lived rent-free in my brain since I first read excerpts of it for class when I was doing my undergrad, more than a decade ago now.

Two questions guide this book: (1) Whom and what do I touch when I touch my dog? and (2) How is "becoming with" a practice of becoming worldly? (When Species Meet 3)

Because dogs have now re-entered my life through the introduction of Pippin into the ménagerie of my household, I wanted to revisit Haraway. I was actually planning on re-reading my extremely damaged and beloved copy of Companion Species Manifesto, because it is pretty much as short as my free time, now that puppy is in the picture, but I could not find it. I know I had it relatively recently on my desk because I was recommending it to someone back in October (November? September?), but the book seems to have gone on an adventure, so I defaulted back to my other well-loved Haraway book, the comparatively beefier When Species Meet.

When Species Meet helped me put into sharp relief the nonhuman as a concept — and, like the Cyborg Manifesto, also complicates and deepens our understanding of ourselves as knotted beings, pluralities of ambulatory earth and bacteria — in relationship with "becoming with" (see quote above) — and just as importantly as "in companion with."

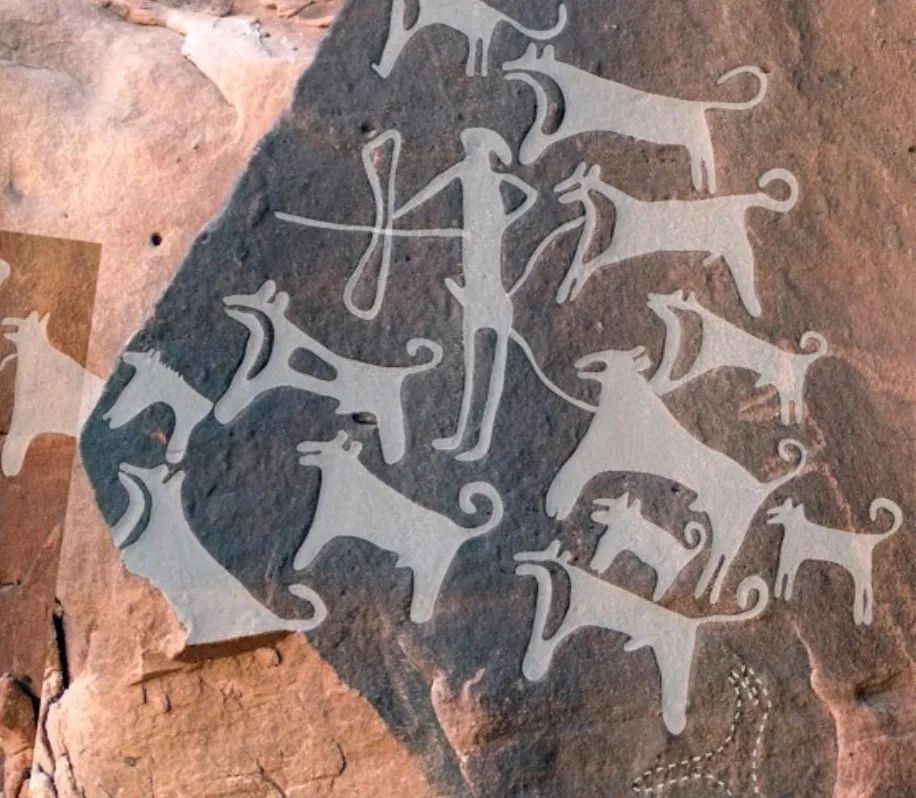

Dogs have been with us (us as in the human species) for at least 10 000 years. There was this incredible image in National Geographic that popped up on one of my feeds, of cave art in modern Saudi Arabia showing packs of humans and dogs (on leashes!) Dated at around 8 000 years, it might be one of the oldest cave paintings chronicling the domestication of dogs:

Some times, when I behold Pippin, my 5 and a half month old puppy, I can't stop thinking of the fact that our two species have traced many paths alongside each other on this planet for tens of thousands of years. We've domesticated each other, and made meaning together. Getting a hunting a dog seems particularly poignant, when I look at that cave painting. I don't necessarily have the vocabulary to describe exactly why — I'm probably overly romantic in my sensibilities — but I keep thinking of Donna Haraway's meaning-making of knotted, entangled beings. As Haraway asks, who will "we" become when species meet? (When Species Meet 5)

Who will Pippin and I and my fluffy mouse-hunting cat and my sweet partner become all together, in the mundane every-day sense?

Several years ago, I had an extremely fascinating (and worldview-shifting) encounter with working sled dogs. I went dog sledding for the first time since I was a child. Before we left, I was given a crash course on the basics of how to work a sled, when to push, how to signal the dogs, how to help. It was an extremely cold day (with windchill, -27 degrees Celsius) and it was my first time working a dog sled. I made a lot of mistakes, as is completely normal for beginners. I keenly remember the head dog, Luna, a tiny husky, shooting me what I can only describe as an absolutely exasperated look after my fifth or sixth big mistake during an uphill turn. She not only tolerated all my mistakes, Luna anticipated and corrected them. I realized in that moment that the dogs were my teachers. I may have been "in charge" of the sled (LOL), but in fact, with that exasperated look behind her shoulder, Luna was resigning herself to having to correct even more mistakes.

When I (sort of) grew out of the typical childish Lassiefication — anthropomorphization — of all dogs as best friends forever in dog-shaped containers, I tended to default to a view of dogs where humans are teachers (assis, couché, à pied, etc.) and decision-makers responsible for all interactions across what Bruno Latour calls the Great Divide (society versus nature, human versus nonhuman). I'm thinking of Isabelle Stenger's bridge-making in Reclaiming Animism: by defining how the bridge works, you're assuming (1) that not only is there a divide and need for a bridge as you define it, but that (2) that your bridge as you (and society, and made-for-tv movies, and family lore, etc.) define it is the only opportunity and modality for relationship.

Companion comes from the Latin cum panis, "with bread." Messmates at table are companions. Comrades are political companions.(When Species Meet 17)

When you break bread with your companion at table, when you share precious ressources (fresh clean water, good food, shelter, a million squeaky dog toys), you are also expressing respect for your companion, for the meaning that you are making together. I come from a family where meals were always shared, and conversation at meal times always long. Sharing food was and is essential to the meaning-making of kinship bonds, with family and second cousins and mentors and godparents and old family friends and new family friends.

Species interdependence is the name of the worldling game on earth, and that game must be one of response and respect. That is the play of companion species learning to pay attention. (...) I am not a posthumanist; I am who I become with companion species, who and which make a mess out of categories in the making of kin and kind. Queer messmates in mortal play, indeed. (When Species Meet 19)

So I watch my puppy, and try to soak up as much as I can about my new messmate, my new companion à table. Response and respect are only possible with reciprocity, observation. Perhaps the bridge against Latour's Great Divide can be shaped by several beings, human and nonhuman. Or perhaps we will learn that the Great Divide is a shallow stream, and we can wade or hop across.

References

- Donna Haraway, When Species Meet (2008, University of Minnesota Press)

- Isabelle Stengers’ “Reclaiming Animism” (July 2012)