Walking Paris

We started walking near the Trocadéro, the Eiffel tower an uneasy metal clarion rising through a misty November sky.

Creímos en las sirenas

que cantan entre las olas

Sus cantos nada nos dieron

ni ayer ni ahora

Somos los mismos que el viento

Nos tiró en las mismas olas

Los hijos pobres del mar

De ayer y de ahora

—Rafael Alberti

We started walking near the Trocadéro, the Eiffel tower an uneasy metal clarion rising through a misty November sky.

We did not cross the river to the Rive gauche, opting instead to walk along the Seine on Avenue de New York. The rain began to fall, then, but only for a few minutes at a time. We had no umbrellas.

We passed the Palais de Tokyo and the contemporary museum, but kept to the side of the water, walking sometimes on sidewalks and sometimes on muddy lawns under the watchful eyes of statues, including one of Lafayette gifted to Paris by the American government. We walked past the Grand Palais and the Palais de la Découverte. I have faraway memories of visiting an exposition of trains and planes there, almost two decades ago when I was probably not yet ten, and of marvelling at how timeless everything felt. The exact details of that memory may be a little foggy now, but I remember that timeless feeling acutely. I relive it over and over again whenever I return to walk the streets of this city.

We kept the Pont de la Concorde to our right as we kept walking towards the Jardin des Tuileries. We stopped by the ferris wheel to grab coffee and hot chocolates and a crêpe which we shared under the rain cheerfully, before we walked towards our destination of the morning, the Jeu de Paume, a photography and video art museum where we planned on spending the late morning with the exhibit Soulèvements.

« Soulèvements » est une exposition transdisciplinaire sur le thème des émotions collectives, des événements politiques en tant qu’ils supposent des mouvements de foules en lutte : il y est donc question de désordres sociaux, d’agitations politiques, d’insoumissions, d’insurrections, de révoltes, de révolutions, de vacarmes, d’émeutes, de bouleversements en tous genres. (Source: soulevements.jeudepaume.org)

The exhibit was a bright, soothing moment on an already dreamy day. This trip to Paris offered us a brief break from the emergent fascist and imploding capitalist reality of North America (with the disturbing understanding that the situation in France is a veritable parallel that whispers: won't be much longer, now) and the textured history of popular uprisings at the Jeu de Paume offered an oasis of remembrance—just for a moment—with which to brace ourselves for what inevitably comes next.

Notably, the exhibit featured a very fragile daguerreotype captured the 25th of June, 1848, titled La Barricade de la rue Saint-Maur-Popincourt avant l’attaque par les troupes du général Lamoricière. It is thought to be the very first "photograph" of a protest (or riot) ever taken. We left the exhibit only to have to ask to go back inside, as we very nearly missed our chance to see it, hidden away under a black velvet curtain to protect it from the ambient lights that would degrade it beyond salvation.

We left the Jeu de Paume for the second time and took the métro—comparing the Paris métro of my childhood memories to her today remains an interesting exercise—for a few stops to bring us to the Marais. The swamp is but a memory now, long ago built upon by such kings as Henri IV and Catherine de Medici. We walked through the Sunday crowds on car-free cobble streets until we reached Place des Vosges, where Victor Hugo's house is still maintained by the city of Paris.

We kept walking, the rain lessening into a comfortable fog, and we decided to return back to the Seine, a new destination in mind. Our steps took us to Saint Antoine, and then down rue du Pont Louis-Philippe. From the bridge we could see behind seagulls, on the ancient site of Roman Lutetia, the twin bell towers of Notre Dame de Paris.

We crossed the Île Saint Louis and on the next small bridge there was an accordion player, playing the enchanting and now classic Yann Tiersen piece La Valse d'Amélie. We listened a while, watching the current of dark river waters disappear under the bridge, and laughed at the lovers we saw kissing on the shores of the small island, huddling together for warmth on this cold day.

We crossed over to Île de la Cité and meandered along the Quai aux Fleurs until we turned left, towards the cathedral, passing stands and stalls named after Hugo's famous characters, Quasimodo and Esmeralda.

We only spent minutes gazing the face of Notre Dame herself. Yellow evening lights were lit throughout the square, and we finally crossed over to la Rive gauche, hoping to make it to Shakespeare and Co, which I had never been to before but have heard about. We stood in line outside the bookstore, waiting to be let inside, grateful that the rain had stopped.

A shopkeeper came to tell us we could enter. The shop itself is small and cozy and crammed full of books, and boasts the distinction of being the oldest English-language bookstore in Paris, as well as a bastion of literature, poetry, and resistance. The bookstore's founder, Sylvia Beach, opened the shop on the 19th of November 1919. Sylvia Beach was a queer American woman who lived with her French lover Adrienne Monnier for 36 years, until Monnier committed suicide. The bookstore was closed during the Nazi occupation (Beach herself was sentenced to an internment camp for six months), but was eventually reopened in its current location, within sight of Notre Dame de Paris on the shores of the left bank.

This bookshop also holds a special place in my heart as the birthplace of my favourite English novel, James Joyce's Ulysses—the story of James Joyce's relationship with Sylvia Beach and her bookstore takes on legendary proportions even beyond the tumultuous events that surrounds Ulysses' original publication.

In the nineteen-thirties, the flight of Americans from Paris and the arrival of troops drove sales into the ground, although the shop retained its reputation as a clubhouse for literary power. When Beach told Gide that she was thinking of closing shop, he got up a committee of men connected to publishing to subscribe as friends of the library for 200 francs a year. Beach survived on this support during the occupation, helping refugees and keeping a Jewish assistant on payroll. Then in 1941, when Beach refused to sell a German officer her lone copy of Finnegans Wake, which she had displayed in the window, he promised to return and confiscate her merchandise. Within two hours, Beach and her friends had stripped the store of its contents, taking even the light fixtures. That was the quick and quiet end of Shakespeare and Company. Eventually Beach was taken to an internment camp—the transgression was not the book but the assistant—where she spent six or seven months, tending to the sick and delivering mail. On her release she spent a period in hiding before returning to the rue de l’Odéon, where Monnier still lived. Their quarter of Paris was the last to throw off the occupation. (Source: modernism.research.yale.edu/wiki/index.php/Sylvia_Beach

To my joy and surprise, I discovered that Shakespeare and Co was selling copies of Ulysses' 1922 unabridged republication of the text. I left the bookstore with two books (only two, as it had been a long day and my tiredness was forcing my book-lusty brain into being reasonable), a copy of Warsan Shire's completely sublime teaching my mother how to give birth and this republication of Ulysses, which I'm now rereading with unabashed delight. I believe it is using the original printing plates from 1922 and there are typographical differences that differ from my Penguin version of the novel. Indeed, when I open the text, behind the original front matter, is a note signed S. B. which reads: "The publisher asks the reader's indulgence for typographical errors unavoidable in the exceptional circumstances."

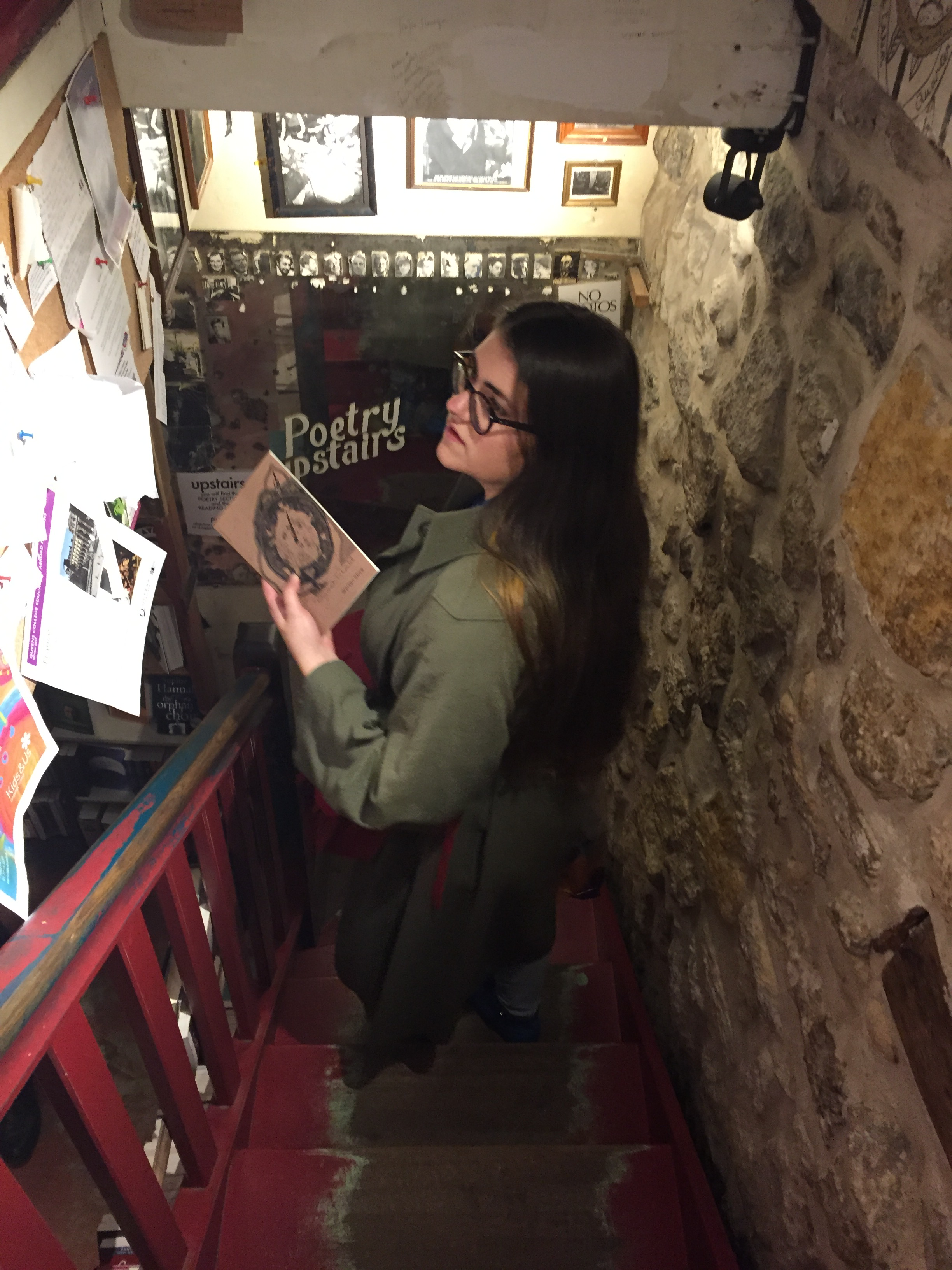

A picture of me on a staircase in Shakespeare and Co, holding a copy of Warsan Shire's teaching my mother how to give birth and reading the bookstore's community board.

A picture of me on a staircase in Shakespeare and Co, holding a copy of Warsan Shire's teaching my mother how to give birth and reading the bookstore's community board.

Our walk did not quite end there, after we left the bookstore. We eventually walked back to the north shores of the Seine into a darkening night. Walking through Paris on the 13th of November, 2016 was a pilgrimage that, without my realizing or planning for it, calmed my anxious heart, and I end the recording of it on the steps of an English language bookstore on the heart-side of the Seine.

I leave you with Warsan Shire to mull over, to breathe in and to exhale, to punch you in the gut:

I hear them say go home, I hear them say fucking immigrants, fucking refugees. Are they really this arrogant? Do they not know that stability is like a lover with a sweet mouth upon your body one second; the next you are a tremor lying on the floor covered in rubble and old currency waiting for its return. All I can say is, I was once like you, the apathy, the pity, the ungrateful placement and now my home is the mouth of a shark, now my home is the barrel of a gun. I'll see you on the other side.

—Warsan Shire