The Cyborg and Colonization: Mass Effect Andromeda Play-through Notes

Oh, wonder!

How many goodly creatures are there here!

How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world,

That has such people in ’t!

The Tempest, Act 5, Scene 1, 188-191

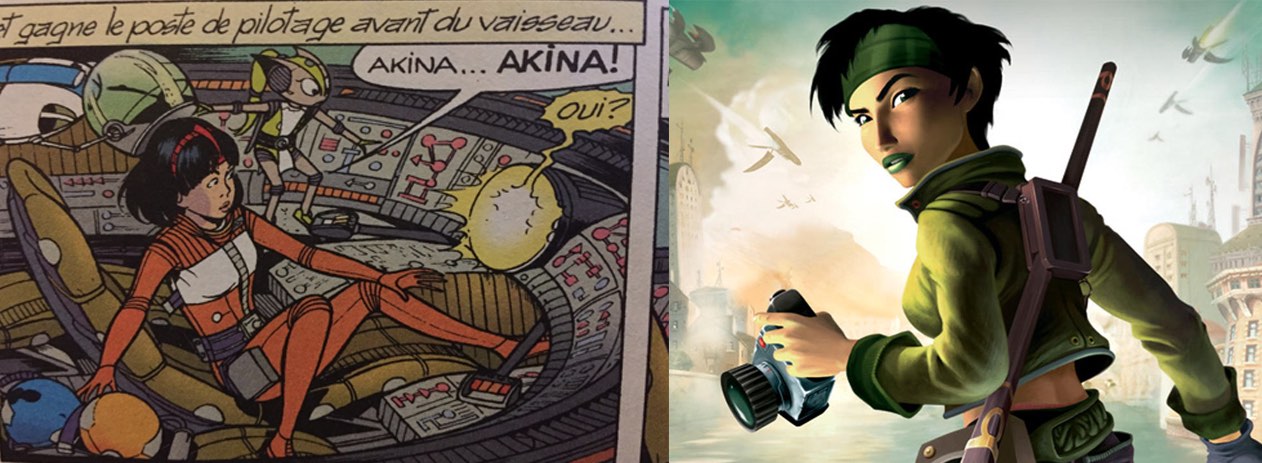

One of my earliest memories as a child is that I’m sitting in a garden in Lorient, doing my best to cradle my only copy of Yoko Tsuno, La porte des âmes, from damp, rainy fog, and daydreaming about space travel, aliens, reincarnation, and the way machines and the mind might interface one day.

I've kept that very same volume of Yoko Tsuno with me for decades.

I've kept that very same volume of Yoko Tsuno with me for decades.

Fast-forward to 2011: it took me hours to install and start up Mass Effect 2, and by the time the game introduced me to the Normandy SR-2, it was the wee hours of the morning and I felt a familiar tug in my chest. Like I was that kid in the garden in Lorient, clutching my Yoko Tsuno, and thinking about space. It was my first time playing a Mass Effect game. Friends of mine had convinced me that playing ME2 before the original Mass Effect would be just fine, and it was. Ever since, Commander Shepard and the crew of the Normandy have a special place in my heart alongside those other science fiction heroes of my childhood: Yoko Tsuno, Jade, and Laureline (to name but a small few.) And, despite all the bad hype surrounding the continuation in the Mass Effect series and the controversy over the ending of Mass Effect 3, I knew I wanted to play Mass Effect Andromeda when it was released.

I have no interest in writing a review for Andromeda—other talented writers will soon publish (if they haven't already) critiques assessing and reviewing Andromeda's merits as a video game and its social and cultural relevance. Instead, these are play-through notes documenting some of my thoughts while playing the game. And, because this is a log of sorts, expect spoilers, some major, to show up beyond this point.

Sara Ryder

In honour of the legacy set by such characters as Yoko Tsuno and Beyond Good and Evil's Jade, I wanted to play a Sara Ryder that reminded me of them.

In terms of the characters abilities, I simply can't resist playing a biotic every time in the Mass Effect universe. Charging into battle with the power to affect, warp, and twist gravity to fling enemies left and right is just the coolest ability. It also helps that I run out of bullets constantly in-game, so I like a battle-style that gives me a lot of back-up options.

I found the very awkward but often earnest Sara Ryder to be endearing. At 22 years of age (minus 600 odd years in stasis), I believe she's the youngest member of the Tempest crew and the youngest of the Pathfinders, and I selected all of her dialogue keeping that in mind. Most of the time she came across as someone who has not quite grown comfortable in their own skin, and I found the overall effect rather charming. I was amused to find that she was sometimes interpreted as being a young, posturing hothead—when in truth it seemed like she was actually compensating a lot for her inexperience. At times, especially with regards to the political situations surrounding Kadara port and New Tuchanka, Sara did not have the kind of experience to guide her in situations where she was being taken advantage of. She also lacked any sort of affinity for political tact or delicate political situations. I liked that I could play a character whose idealism had not yet been tempered by intergalactic bullshit yet, but who was also in the process of discovering the limits of that idealism.

I was also intrigued by the Ryder family. The more I learnt about the parents and the twins, the more I found their particular dynamic interesting. Alec Ryder's tense relationship with fatherhood lingered even past his death in how it affected his children and even other members of the Tempest's crew.

I appreciated that the game allowed the player to decide the extent of the main character's "daddy issues" and how it would affect the dialogue—with my Ryder I decided that she was the kind of person who wouldn't let herself dwell on her admittedly poor or awkward relationship with her father when well over twenty thousand people relied on her to survive, and especially when her father literally sacrificed himself so that she could survive. I appreciated less that the game didn't explicitly show any references to mourning or even dwelling, even in private, except for some very oblique references while investigating your father's quarters, speaking with Dr Lexi about the experience accessing your father's memories, or the ability to wear your father's N7 armour.

Speaking of, a really interesting bit of gameplay is the shit you have to deal with from some of the humans if you walk around wearing armour refitted from your father's N7 armour. As a biotic, it was some of the best biotic-boosting armour in the early game, so I ended up wearing it a lot during those early encounters. I was really surprised when some humans gave me shit for it! In-universe, the N7 insignia and designation is the most prestigious human military designation in the Mass Effect series, and it was quite a kick to get dirty looks for being a 22-year-old wearing a military symbol I did not earn.

Remember Conrad Verner from the first Mass Effect game, wearing the N7 armour without having earned it? Interesting to inadvertently be on the other side of that equation. One player recorded the exchange with August Bradley on Eos when he calls you out for wearing the armour.

SAM (Simulated Adaptive Matrix)

There are several ways in which Mass Effect Andromeda missed an interesting opportunity for storytelling and ethical pondering with regards to their treatment of artificial intelligence. From what I've gathered from playing the game and reading the codex, SAM is an "unshackled" artificial intelligence that has a direct link to the Pathfinder's brain. In the Mass Effect universe, "unshackled" is a term we've seen before. In the original trilogy, it was a term used to describe AI who had gone rogue, or AI whose "shackles" (blocks in their programming which prevent them from harming or directly disobeying their fleshy creators) had been removed. The allusions to slavery (not only in this series, but elsewhere in science fiction and even actual science) are deliberate.

Karel Capek’s 1920 play, R.U.R., introduced the term “robot” to describe the biological workers built and sold by the Rossum’s Universal Robots company. These robots stage a global uprising, choosing to annihilate their human creators, instead of fighting for equality or independence. The concept was arguably more surprising in the 1920's, when the machine uprising trope hadn't permeated pop culture. But whatever role R.U.R. had in kickstarting that tradition, it may have been simply borrowing general themes from older stories, and fictional robots by another name. From the Golem of Jewish myth to Frankenstein’s hyper-intelligent, lab-birthed monster, there seems to be a built-in assumption that artificial intelligence will lash out. Erik Sofge, "Rise, O Machines: Why Hollywood's Best Robot Stories Are About Slavery"

So, the Initiative (the not-at-all creepy sounding name for the for-profit colonization efforts in Andromeda, and I will expand more on this later) have tasked four Pathfinders (one human, one turian, one asari, and one salarian) to explore these brave new worlds with this "unshackled" artificial intelligence symbiotically connected to their brains. In other words, SAM hears, sees, smells, and feels every experience lived by the Pathfinder and can even affect the Pathfinder's body chemistry and physiology. It's a non-optional perk of the job: forcing the removal of SAM from a Pathfinder's brain can be so destructive as to be lethal.

I was surprised how tame the reaction of the Tempest's crew was to the presence of SAM, and made me think about the AI's personhood in-game. Even Drack, who voices his discomfort regarding the existence of the AI, doesn't make much of a fuss except for occasionally whining about it (and the whining is always done using the most general and unthoughtful of arguments: that it can't be trusted because it is an AI.) None of the crew members remark or deplore the fact that SAM is hearing, seeing, and recording EVERYTHING the Pathfinder experiences. Electronic surveillance may not be a hot-button topic in the Andromeda galaxy, but when Sara Ryder wasn't on active duty, I found it interesting that no mention was made to the fact that SAM is nonetheless always on, recording everything: every personal interaction, intimate detail, even every sexual encounter, was now recorded somewhere in SAM's memory. You don't need to open a specific channel on your omni-tool or coms terminal—characters (even other than Ryder) just have to call for SAM wherever they are on the Tempest, and the artificial intelligence will respond. At one point, Lexi even apologizes to SAM for implying that SAM didn't have feelings or didn't care about the human Pathfinder.

But what does it mean about personhood if there is one person who can see everything, hear everything, and remember everything that ever happens around them? Imagine if SAM was not just a sentient, hyper-sophisticated bit of hardware and software but just a person running around the Tempest, plotting navigational courses and performing an analysis on Remnant technology while also watching your every conversation and observing you when you're having having sex. What does it mean about personhood when privacy disappears? When boundaries and limits are nonexistent? It is also unclear in-game how much access SAM has to Ryder's thoughts. We also don't know if SAM is truly "unshackled"—he has certain blocks on his own abilities and memories imposed by Sara's father, and it is never addressed if he could break away from the Initiative and abandon his mission if he wanted to. We know from the game's dialogue that he considers the mission Alec Ryder designed for him his purpose in life. But could he abandon it if he wanted to? A choice is only real if it can be made freely.

In that same vein, what does it mean that SAM can kill Sara Ryder on purpose if he wants? In the game, Sara develops a personal and trusting relationship with the AI. She trusts SAM to have her back. It's one thing if SAM is truly an individual who can always make his own choices—but what if he's under Initiative control? What does the nature of their link, which can mortally harm Sara, mean if he doesn't have complete agency?

The AI is housed on an Initiative ship which means that, to some extent, even if SAM is a person who feels a protective loyalty to Ryder and her people, everything that he records is the property of a for-profit company that we eventually learned has been funded by an illusive, mysterious backer on Earth—and as we discover in the game, the people who founded the Initiative were or are shady, dishonourable and murderous characters. Do we know what SAM's ultimate purpose is? How do we reconcile a definition of personhood with the fact that SAM is the property of the Initiative? We know that Bioware has addressed these questions before in previous games with EDI, the Normandy's AI or brain. The ship Normandy and EDI, in essence, was a sentient being, a person (even before she acquired her mobile platform that gave her artificial tits.)

Overall, I was happy with the "cyborg Pathfinder": the joining of two people: one artificial, one fleshy—into one being, even if I thought they could have been much, much, much more daring in their execution of the concept. It opens up all sorts of avenues of investigation for future games and (more importantly, as fans often take these kinds of questions and run with them) fanfiction.

The cyborg does not dream of community on the model of the organic family, this time without the oedipal project. The cyborg would not recognize the Garden of Eden; it is not made of mud and cannot dream of returning to dust. Donna Haraway, The Cyborg Manifesto

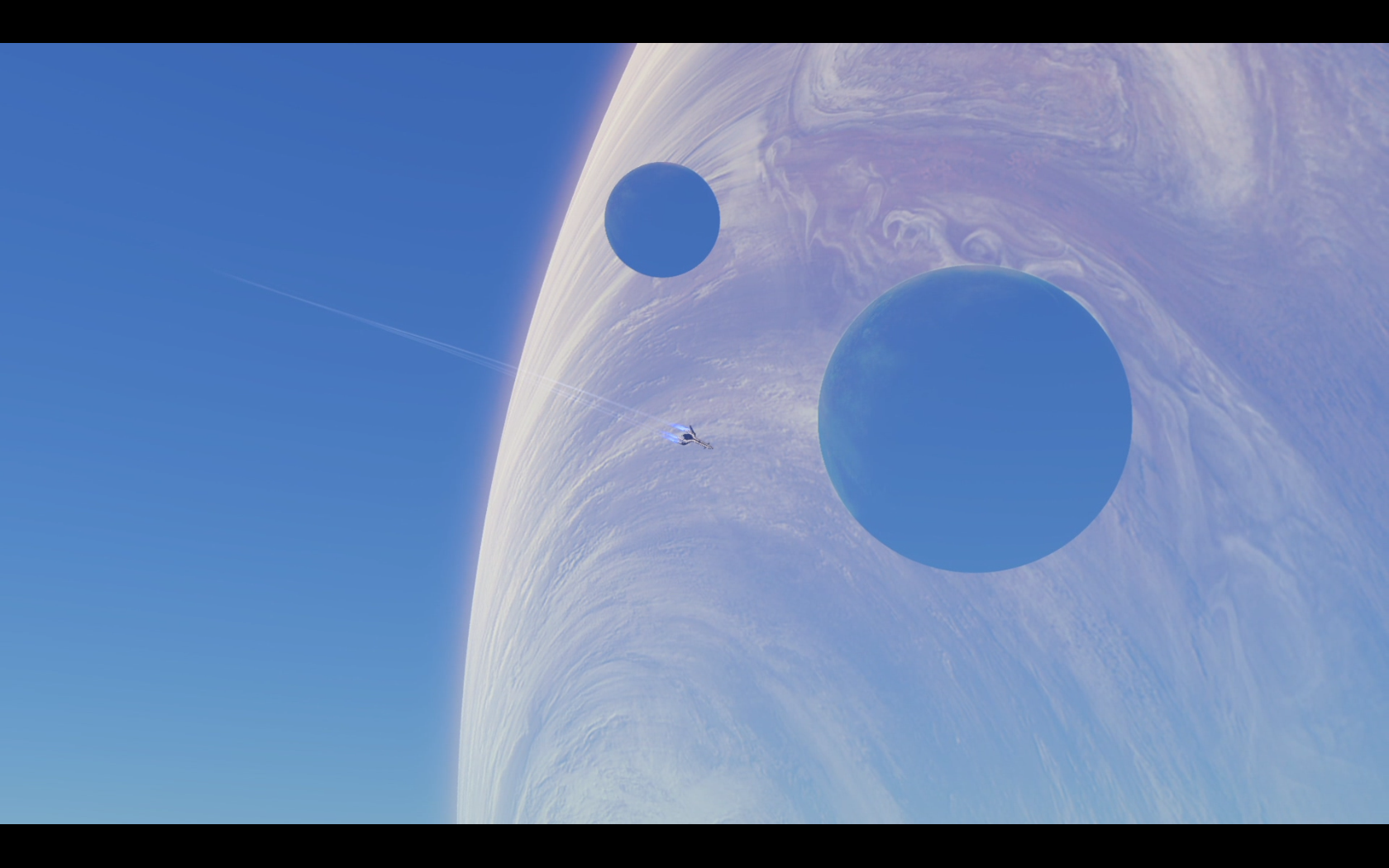

I found myself thinking about the cyborg a lot while playing Andromeda, especially as we unearthed clues into the Remnant and their artificial yet also not artificial planet. The natural and the artifical are blurred together in the Heleus cluster as the planets themselves are revealed to be a sort of networked cyborg through their interconnected Remnant vaults. I appreciated that greatly, and wished the game had even pushed the execution of this further. Mass Effect 3's ending proposed a complete synthesis of inorganic life and organic life; but it felt like a forced, abrupt non-option, interesting but ultimately ethically reprehensible. (Arguably, each of the three Mass Effect 3 endings are ethically reprehensible.) I was happy the game developers were revisiting this subject in the Heleus cluster in a way that feels much more open to discussion and reflection and further expansion in following games.

On another level, Sara Ryder as a cyborg also reconciles the gameplay with the story, and offers an explanation for the fact the Pathfinder is catastrophically devastating in battle. It makes rubbish sense that squads of three people can mow down dozens or even hundreds of enemy robots or enemy aliens in a few hours. If we know that the Pathfinder has an AI in her brain that assists her, then it helps address that particular bit of video game silliness.

Colonization

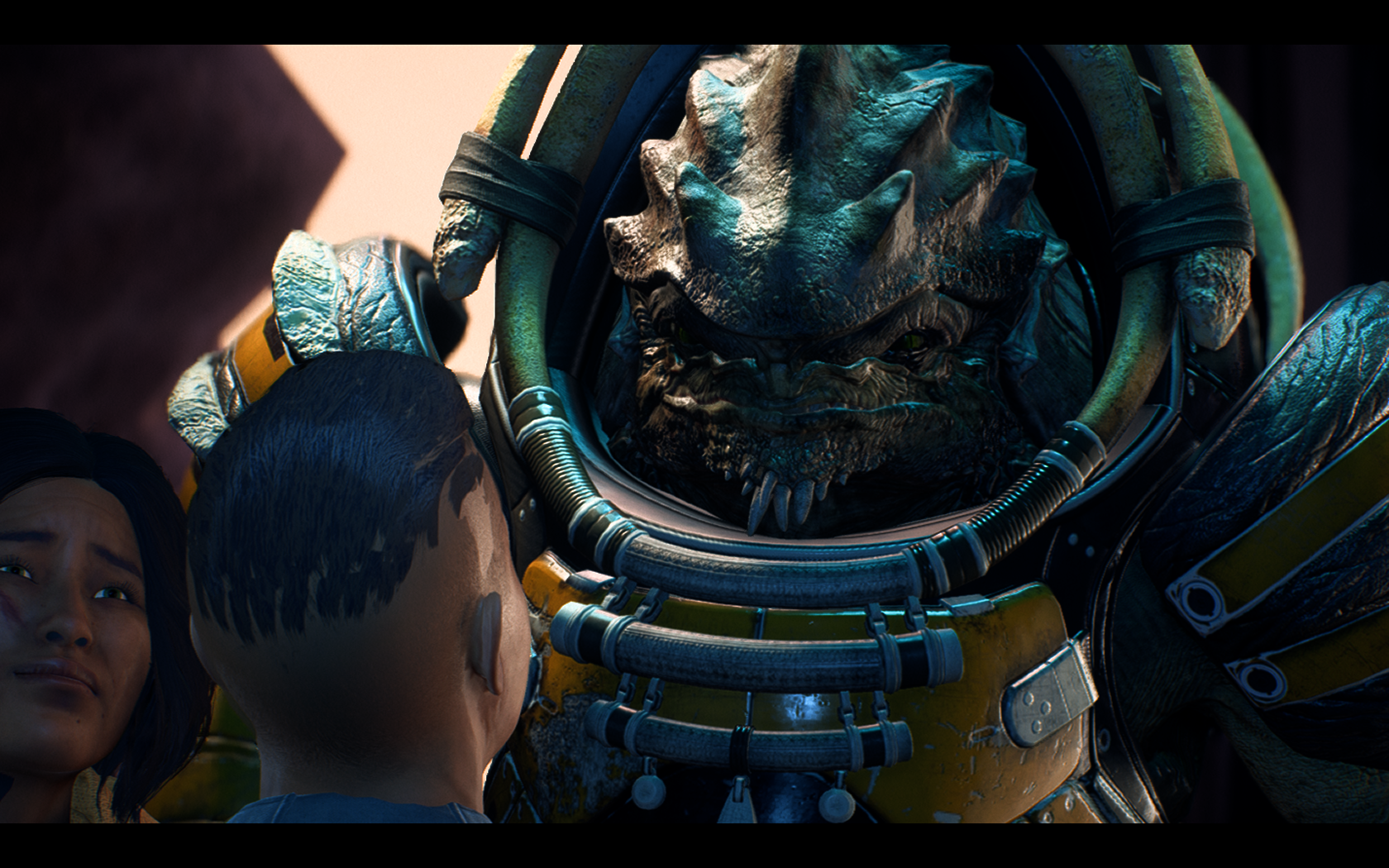

In what is probably in my top five favourite moments in Mass Effect Andromeda, Sara Ryder and her 1400-year-old krogan friend Drack are in a grungy bar at the ass-end of the universe, and take on the entire bar in a good, old-fashioned fist-fight. Let me tell you: you want to get into a brawl with a 1400-year-old krogan at your side.

And, what's more Western than a grungy brawl in a saloon on hostile land?

Many speak about Joss Whedon's Firefly as being a particularly cogent expression of the "Western in Space!" subgenre of science fiction, but the reality is that most science-fiction has flirted with those themes since its earliest beginnings. A "final frontier" and space gunslingers are extremely familiar by now, and Andromeda doesn't just flirt with the motifs and tropes—the game is built on them.

Andromeda's approach to the question of settling the land and relocation to the hostile planets is actually quite familiar. In an article on the movie The Martian, author David Sims writes that:

While space is an alien landscape, Mars is always a recognizably human one, warped to the harshest extremes: Survival is within reach, but complicated by the elements, or natives, or both. Why the Mars Movie Is the Space-Age Western

Though the events in the game do not take place on Mars, this is the crux of Andromeda: Habitat 7 and the other "garden worlds" of the Heleus Cluster were selected by the Initiative back in the Milky Way for their resources and exploitability. But as they arrive out of dark space, they discover that not only are the planets extremely dangerous, and not only are some planets inhabited, but that there is a desperate war going on between another colonizing, genocidal force and the indigenous Angara. This seems to be a tool the game developers use to temper an otherwise straightforward narrative that would paint the Milky Way colonists as the "bad guys."

The Western genre is the genre of colonization. At several points, the game is actually pretty explicit about it. Even with the planets warped to the extreme by the war taking place, the Milky Way arrivals still have to stake their claim there to survive. The game is clear: they cannot survive in space. Alec Ryder, Tann, Addison, and the Initiative broadcasts paint a pretty picture of exploration and "the best humanity has to offer"—but it doesn't hold up under scrutiny. As one of the native Angaran, Evfra de Tershaav, reminds Sara Ryder when she protests that the Milky Way people did not come to Andromeda as conquerers:

Efvra: "The Initiative." Sounds so unthreatening. Like a city planner meeting.

Ryder: That's kind of what it's meant to be.

Efvra: City planners don't walk around in battle armour with rifles on their shoulders.

Ryder: Depends on the city. My point is: we travelled through dark space to build something here.

Efvra: That's what invaders always say. At first.

Ryder: We're not invaders.

Efvra: (sarcastically) Of course.

In Andromeda, there are good colonists and bad colonists. Because this is a video game, Ryder and her team and the rest of the Milky Way colonists are the good colonists. The Kett, a force not unlike the Reapers and Collectors of the original Mass Effect game, are the bad colonists. You can tell the Kett are the bad guys because their ships and technology are uglier and they kidnap the locals in order to do genetic experiments on them that mutate their victims beyond salvation. They also shoot and attack cities and planet. Bad guys are very different from the good guys, right?

At times, Sara Ryder engaged in fights to the death with three different kinds of enemies: the Kett, Remnant killerbots, and local Angara who did not see the difference between Milky Way aliens and the Kett. In that moment, when my character was shooting the angry, distrustful Angara dead, they were right. I, and the other Milky Way aliens, are no different from the colonizing Kett. Perhaps video games are particularly suited to narratives of colonization because we have been refining and perfecting their ability to express war and violence, and colonization is a bloodthirsty enterprise.

At the end of the game, you have the option to nominate the first member of a new interplanetary government of sorts. This person would then push forward the creation of a truly democratic interplanetary order where each population or civilization or planet could then nominate their own representatives. The Initiative strongly suggests you select one of their high-level associates for this process, but instead I chose an Angaran cultural and scientific leader, the Moshae, against the wishes of the Milky Way Initiative and many other factions. Sara Ryder's reasoning? The Angara were here first.

But, as the Moshae herself later reminded her: despite Sara Ryder's hopes that the Moshae would inspire unity and solidarity among the Angara and the Milky Way people, she does not reflect all of the Angaran people, such as the Angara who wanted Ryder dead or those Angara who were killed by Milky Way colonists, including Ryder. The Kett are now a postponed threat, kicked out of Heleus for a while. But now the Milky Way colonizers have access to extremely powerful weapons in the form of the Remnant's technology. Who is to say that in a few decades, the Milky Way colonizers and their new government won't be the violent, colonizing, subjugating force the Kett was? We know from previous Mass Effect games that the salarian, asari, turian, krogan and human governments are far from enlightened.

The possible abuses of power with regards to the Milky Way colonizers' access to the Remnant terraforming technology parallels the way in which SAM—likely inadvertently—spies on Sara Ryder and the crew of the Tempest for the Initiative. The planets of Heleus are cyborgs themselves, connected to the Remnant hub now under the control of the Milky Way Initiative. What does it mean for interplanetary politics when the Angara resist Initiative control, and the Initiative possesses the ability to weaponize your entire planet's atmosphere, ecosystem, and biochemical nature against you? What does it mean for choice when the threat of that kind of retaliation exists, despite promises from everyone to be on their best behaviour? Can the Angara and the Initiative truly have a relationship of equals when the Initiative now literally inhabits the centre of Remnant power and technology?

These are questions Mass Effect Andromeda does not answer explicitly, but, let me tell you, I am really looking forward to the fanfiction.