Taking Up Space: Tara McGowan-Ross speaks about "Girth"

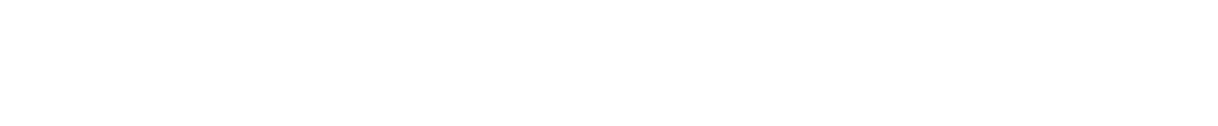

Girth is the first book by Tara McGowan-Ross, a Mi'kmaw poet and philosopher who lives in Montréal, and who I met in the Creative Writing at Concordia University.

imagine a girl, then imagine something

not a girl, but girlish, substantial, globular

"girth”

When Tara and I meet to talk about her book, on the first of March, 2017, it’s a freaking rainy day. In March. In Montréal.

As disappointing as the weather is, it doesn’t even come close to bothering us as Tara dries off and settles in my living room with a hot cup of tea. I fiddle with the tape recorder (well, okay, it’s my phone) and make sure everything is working before we get started.

Girth is the first book by Tara McGowan-Ross, a Mi'kmaw poet and philosopher who lives in Montréal. Tara and I met at Concordia University where our undergraduate degrees overlapped. She was a philosophy major with a creative writing minor, and I was a creative writing major who ended up taking a bunch of philosophy electives. We’ve shared courses in both departments, and I’ve had the pleasure of witnessing Tara in action in both a creative writing workshop, a philosophy class, and during various political actions and demonstrations over the years. Tara is the kind of person who puts me at ease, inside and outside the classroom. She's got a beautiful, loud laugh, and I remember I looked forward to class when Tara was there—she just made it more interesting.

Our conversation over Girth was as much an enjoyable discussion about poetry, writing a book, philosophy, student strikes, people, and bodies as it was an occasion to catch up with Tara and look back on our undergraduate degrees with somewhat exasperated fondness.

This particular digital offering is a collage—part historical accounting of the student resistance of 2015, part transcription of a conversation about poetry, making a book, and mental illness, and part small glimpses of the poetry from Girth, a journey in and of itself. All the poetry quoted can be read in its entirety by buying Girth by Tara McGowan-Ross, Insomniac Press, 2016.

The worst part is when

your voices all seem to rise in harmony,

when you start up some old french song

about the bourgeoisie that your father

used to sing, and people you've never met

remember all the words. When you're walking

with a couple thousand of your closest friends,

circumnavigating a world that it feels

like you could rule. When you say

À qui la rue? À nous la rue and it feels

like the truth."night demo VII"

Printemps 2015

Tara McGowan-Ross: "I think that, very nebulously, one of the main reasons I had wanted to move to Montréal in the first place was because of the 2012 student strike. I think that while I did my best to do research and find out why people were mobilizing, a lot of what attracted me to it was the mobilization in general. It was this incredible act of just saying no to something that you felt was unreasonable, and it was also this act of doing something, well, that kind of felt unreasonable in response. If I’m trying to be self-critical and honest, that was a big part of what attracted me to the movement in general. By 2015 I also had seen, in the past two and a half years that I’d been in university up to that point, what an effect austerity measures had on people at a very personal level—people were concerned about not being able to give their children everything that they wanted to be able to give them, and people were feeling like their research was suffering and that they were being taken advantage of. There are a lot of things that you give into an institution that they were never going to get back if they had their compensation and hours cut. I was riled up enough to want to cause a ruckus."

In March 2015, students from several departments at Concordia University in Montréal held general assemblies on whether to join a province-wide strike movement called Printemps 2015. Several departments voted to strike on April 1st and 2nd. The philosophy undergraduates voted for a weeklong strike from March 26 to April 2, and organized hard picket lines, noise disruptions, as well as overnight demos to protest austerity.

On March 16, 2015, journalist Frédéric Muckle for The Link, Concordia’s University student-run newspaper, was found recording the general assembly of the Undergraduate Students of Philosophy Association (SoPhiA) while they debated whether on not they should go on strike. Approximately halfway through the meeting, someone realised the press had been recording the discussion. The general assembly is open to the public, and while a motion to turn the open session into a closed one failed, the journalist was pressured into deleting their recordings. The event was later reported as follows in the paper by Jonathan Caragay-Cook: "While Muckle technically deleted the recording of his own will, he was put under public pressure to do so. Those not from the student association were asked to sign in with their name and ID number before entering the room."

When I turn to page 25 of Girth, where a section of a poem has immortalized this particular political disagreement, I find myself wishing all the meeting minutes I’ve ever had to read (and, frequently, write) were lines of poetry instead:

Are there media present?

Why are there media present?

Media, where are you?

here

here

You should have revealed yourselves.

Why didn’t you reveal yourselves?

we have a right to be here

it isn’t a closed session

This should be a closed session.

Motion to move into a closed session.

Not seconded.

Discussion.

Unusual. I let myself be heard here, guys, and no one

told me I was being recorded. What

kind of world is this, where we don’t know we’re being recorded?

”GA minutes II”

While listening to Tara and while reading the book, I thought back to the tradition of poetry as witness to history. Girth, whose poems often deal with space—navigating the geography of the body and the student body politic, charting the spaces between people, taking up political space—is also about witnessing, if not a factual retelling of the author’s life, then a factual accounting of the history of a handful student strikers at Concordia who tried to hold onto a fleeting moment of resistance against austerity.

Printemps 2015 seemed to hold all the ingredients for a major repeat of 2012. Ethan Cox of Ricochet Media wrote on the anti-austerity student movement at the time: “All indications point to a major showdown at some point in 2015, one which could have implications for the austerity agenda on a global scale.”

It didn’t.

At Concordia, the strike lasted a week.

I’m sick of proving who among us can love this fight the most.

Our once mighty picket line is now made up of ghosts.

”PICKET LINE DAY SIX”

Tara McGowan-Ross: "I think that there are a lot of reasons why the 2015 strike failed, some that I don’t completely understand, still, and I’m not well-versed enough in the union level of politics because, well, at the union level, there were a lot of problems. There were a lot of different factions all thinking that different ways of doing things were better and they couldn’t see eye to eye. Eventually, someone—some faction—endorsed this concept of “strategic withdrawal.” Somebody gave up, basically, at the union level. Somebody said: “This is too hard, this isn’t working, we can’t do this sustainably. We’re just going to give up.”

"And I think that that particular mindset was mimicked a lot as we went down the chain to the general populace of the actual striking labourers. Everyone was super exhausted because everyone had gone in guns blazing and every night we were going to have a demo and every morning we would block classes—that’s really how it looked at Concordia. And the night demos would go until twelve or one in the morning sometimes, and people were really amped up on the adrenaline of it. I found that I often stuck around to smoke cigarettes with people and talk and go back to other people’s houses and talk more—talk about the resistance, the strike, what you were going to do tomorrow. And then you’d go home and try to do your homework. Even if you were on strike for a week you couldn’t stop doing your work for a week. You weren’t handing in the work and you weren’t going to classes, but you still couldn’t let yourself fall behind. So everyone was running off of two hours of sleep and then we had to get up at 8am in the morning to go block a classroom. People wanted to commit so completely that we forgot that we were all human beings who burn out eventually. We all eventually stop being able to care as much as we did at the start."

"We also stopped being able to treat each other like human beings. There was a lot of in-fighting, especially near the end. There were a lot of bitter arguments between people, and I don’t think they were necessarily caused by any one person’s individual actions as much as they were caused by this really desperate sense of everything not working and seeming doomed."

Questions/Amendments

Not to accept austerity (?)

Not to let this destroy us (?)

Not to let this be the end (?)

To be friends again (??????¿¿¿???¿¿¿¿¿¿)

"GA Minutes III"

Tara McGowan-Ross: "With anything to do with politics, human psychology comes into play —I think building momentum is just so important, and making sure everyone is actually committed, no one is distracted and that the momentum occupies enough of everyone’s brain that everybody just wants to keep going. Putting the strike on hold, “withdrawing strategically” with the intent of going back in stronger later was still the idea when the strikes ended. But now it’s two years later and still nothing happened. People got busy, and austerity measures are now officially in place and getting amped up consistently, both officially and unofficially—it doesn’t necessarily have to be under the same name for everyone to notice that that same thing that caused everybody to worry about is happening. Work gets even harder, and you have to work even harder to stay afloat, and then you’re just too busy and you just don’t think about it anymore. It’s unfortunate but conditions need to be just so for really effective resistance. And you need to know how to keep momentum going, and how to keep escalating and pushing forward. A big break doesn’t do that. Breaking the strike after a week? That’s just not how it works."

"There were a lot of opportunities for momentum that ended up getting quashed by very liberal resistance tactics. Like there was this enormous demonstration, this absolutely huge day of action, a demonstration where hundreds of thousands of people show up, but then afterwards nothing happened!"

April 2, 2015. Photo by AJ Korkidakis

April 2, 2015, was a student-led, anti-austerity march in Montréal which attracted over 75,000 students. I marched that day. I remember walking under the overpass at Berri-UQAM. Another estimated 130,000 students walked out of their CEGEP and university courses that day. The energy was palpable—I remember walking, surrounded by thousands of people, feeling the mild sun on my face and my throat hurt from chanting. It truly felt, in that moment, that another 2012 was around the corner.

Tara McGowan-Ross: "It was the same with the big Women’s March in Washington after Trump’s Inauguration! Millions of people showed up, and then at the end of it people just throw their signs out and go home! How many people just threw their signs in the garbage, got back in their sedans, and then went back to, you know, their data input job in Jersey? How many people just did that as opposed to, I don’t know, fucking staying around in Washington for a few days and talking about it and making connections—maybe I’m just assuming that didn’t happen because that’s not at all what it looked like from the outside. Maybe it did happen but I still can’t see any actual fundamental thing that happened beyond some nebulous idea of “people are getting involved!” I find that very disappointing as someone who is in the “Stay pissed, escalate hardcore, make smashy-smash if you have to” school of resistance."

"That particular brand of resistance is the hardest to maintain because it becomes so visceral that people don’t want to take breaks. And I’m not talking about the three months “strategic withdrawal” kind of breaks, I’m talking about the kind of break that requires people to actually leave the picket line and go home and sleep for 8 hours, and let someone else take your place for a while. Doing the work of getting more people involved in a committed way is a really difficult conversation. In 2015, the majority of philosophy students who showed up to the strike GA voted in favour to strike, but then there were, I think, twelve students who showed up every day to actually do the work. There were around 100 people at that strike GA! If we had 50 people showing up to hold the picket lines, can you imagine what we could have accomplished? I guess they didn’t show up to class, which was one way of participating in the strike, but they weren’t picketing or showing up to meetings."

"I think a lot of the time, from the outside in, when resistance looks really successful it’s always about the message—about the quality of the message, and the heart of all the resisters. There’s a lot that you’re not seeing. I was overjoyed by the steps taken to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline. But all you’re seeing from the outside is all these nice people standing around. You’re not seeing just how much work goes into that, and how much education is going into it, and how many different points of view are being passed around. Optics end up being so important but the optics-based way of analyzing what is going on is leaves out so much information!"

"I would like to participate in some kind of resistance where conflict is handled in a more mature way, and in a way that doesn’t let us forget why we have to be there—I don’t want to say “we have to be united” because that just sounds so liberal and weird, because I think diversity of tactics and diversity of opinion is useful, and obviously you don’t want anybody involved who is being abusive, or shitty, or whatever. But I saw a lot of petty people being really hurt, and as a result picking fights in bad faith. And you can tell the difference. You can tell when people aren’t being honest with themselves. If you have to struggle over differences in the left or in the resistance or wherever, do so in good faith. Shutting down assholes in good faith—that’s fine. But I think there are a lot of people who aren’t acting from a good place and they know it but they are too proud to admit it. I see that a lot."

to leave no good walk unspoiled, kicking the bones aside

as we went, touchy spot, still ringing in your ears as the boomsounded, last door closing. nineteen ninety-six. now everyone

can choose how they learn, by the book or by the streetor by the business end of a rubber bullet. this is still Canada.

I’m sorry. we call a lot of things school.

"nothing happens out of context"

WHEREAS philosophy students acknowledge that university is not what we imagined it would be as children and that adulthood, the real kind, is hurtling towards us with an accelerating and alarming speed and we need to feel something that isn’t sleep loss and gut rot brought on by too much coffee and the truth behind the assertion that maybe it would have been better to study economics in the first place, am I right? ha ha ha. Oh god. Oh god, what have I done.

"STRIKE MOTION"

The things you pour out of you, that you’re never going to get back

Tara McGowan-Ross: "I feel like a lot of my mental health got poured into my undergrad—and I don’t want to necessarily blame Concordia as much as academia in general that Concordia ends up being a vessel for. I feel like I put a lot of personal experience and emotional labour and a lot of hard to quantify but very real intellectual labour into Concordia. I always approached things I had to do for school with a kind of “destructuring” approach. I tried really hard to question things that I was supposed to do in a way I hoped made people think differently about whatever we were supposed to be doing. That was often a service of intellectual labour that I performed and I could see how conversations that I was a part of and the kinds of things that I would put into my work would shift and inform and send movements through the people around me."

"I studied creative writing and philosophy and I feel like this book is tactile evidence of the fact that I was really freaking out the whole time, and I was writing it all down because I had to produce work for school. I feel like I only wrote this book because I went to Concordia and studied what I did—because I was at this university, in this city, in this political and economic and social context, and that I was also writing at the same time. I’ve staked my reputation on it: I’ve written this thing as a result of Concordia and I’m never going to be able to go back to who I was before that."

"I think that I have this compulsion to do everything on the hard mode. I don’t slowly introduce things in my life and see if I can build up to the more difficult thing—no, I love to plunk myself right down into the hardest thing I can possibly do and see if I can figure it out. It’s how I’ve developed certain skills that I have: I learn a little bit of the intro stuff, skip all the middle stuff, and then go straight to the hardest thing and then just like fuck it up royally until I can kind of do it. I skipped a lot of the stuff that you’re sort of supposed to do to be a writer and get into publishing—I just really wanted to write a book and see if I could figure it out."

"The only place I think it might be harder to live than Montreal for this really small-town, impossibly naive young woman who at this point thought that I spoke better French than I did, would probably be New York City. I can’t think of anywhere harder than Montréal. But the payoff was very great. My French has gotten better. I can have a conversation now! I had been stumbling over French for so long and making enormous gaffes and being so embarrassed and people had to switch to English automatically for almost three and a half years and then, when I absolutely had to, I opened my mouth and a bunch of French came out!"

"I think about whether I want to stay in Montréal a lot. I think I want to stay. I would have told you no, a few months ago, but now I want to stay. When I lived in a really small town in Ontario north of Toronto, and then when I lived in Halifax, I got to this place where my life was just so messy. I got to the point where my life was unsalvageable. I just wanted to etch-e-sketch, peace out, and go somewhere else. And that was—a few months ago—how I was feeling about Montréal, but I think I’ve recovered since then. Halifax is so small that when you eff it up once, there’s nowhere to go and hide from it and people don’t really forget. But here in Montréal it’s been easier for me. Two and a half years ago I was having a really hard time emotionally when I was first diagnosed bipolar, and I just decided to move to a different neighbourhood, and etch-e-sketch my life just a little bit by giving up my lease and moving by metro forty minutes away. You can do that a few times in Montréal before you run out of directions!"

You don’t get to just do whatever you want because you’re twenty-five and you smoke two packs a day and you think that means you aren’t afraid of dying. That doesn’t mean you get to just do that to Marx. Just because you have a library in your mile end apartment and a sexy accent and a dubious moral code regarding when constitutes infidelity. You don’t get to do that at eleven fifty-five when your girlfriend is calling you but you keep pressing the mute button and you’re still here at the kitchen table saying

I know what you mean, Karl, but here’s why I think you mean something different.”Karl Marx thinks you’re acting stupid and so do I”

Tara McGowan-Ross: "I got involved politically after I’d been diagnosed bipolar, and I’d been on meds for a bit. I had moved to NDG (Notre-Dame-de-Grâce) by that point, where everyone has a dog or a baby and nothing particularly exciting ever happens and you can just live your life. I was living in the Gay Village before, where it was like DRUGS, AND PARTIES, ALL, THE, TIME! It is really hard to be bipolar and live a life with no impulse control in the Village so I moved somewhere a little bit more “no-impulse-control” friendly. There’s a lot of mental illness in my family—I kind of suspected that I had ADHD for several years. Probably for about a year before I was diagnosed bipolar I suspected that I had ADHD because it would take me so long to focus on anything. My house was always a mess, and I was always a mess, and dating back to childhood my desk was always a mess, my locker was always a mess, and I couldn’t seem to keep track of anything and was really inattentive. I was constantly daydreaming. I’d be daydreaming in the middle of a conversation I was trying to have! That’s apparently the classic ADHD symptoms for assigned female at birth people—they tend to be less outwardly destructive and more inwardly destructive. I was very inwardly destructive, had really low self-esteem no matter how hard I tried."

"But it would come in waves—I would get really fed up with my life and say “Fuck it! As of today, I’m going to get my shit together. As of today, my, shit, is, together!” I would wake up really early, and exercise in the morning, and then clean my whole room, and go to school, and then stay out late, and hang out with my friends, and do a bunch of writing, and buy a new journal, and fill all the pages with stuff, and get a day planner!!! I’d stick to that for a couple of weeks—until I had my longest manic episode, which I realise now what it was. The longest hypo-manic episode I ever had lasted six weeks. It was at the beginning of my third year of university. I barely slept, barely ate. I was drinking so much coffee that it went beyond drinking coffee. I was taking caffeine pills and a nasal decongestant that would boost the effects of caffeine in my body so that the caffeine would affect me more. I was staying up for days on end and I wasn’t eating—but I was reading like crazy and pulling long hours at the library."

"What inevitably happens is I run out of steam—I get sick or all the hyper-positive thoughts I have are undermined in some way. It usually happens where I have one fight where someone gets mad at me for something, and all of that energy shifts inwards really quickly and I start using that energy to beat myself up really hard. I end up so depressed I can’t leave my bed because I’m so physically exhausted. This had been happening on a smaller scale for a lot of my life, but it finally happened to the point where my manic episode was ridiculous. In the process of being manic, I messed up a job really badly for the first time in my life due to my mental health. I kept sleeping through shifts. I had early shifts and I kept forgetting about them because I kept trying to do 1000 things at once and my brain was so scattered. I’d forget about shifts and just not show up. I was babysitting this little boy at the time—I was supposed to walk him to hockey practice and back in the mornings. He was fine without me, he would just stay at home and wouldn’t go, but I really disappointed him and I really broke the heart of this really sweet eleven year old boy. I got really depressed. I couldn’t get out of bed, I couldn’t go to class. I couldn’t do anything."

"It finally got back enough that I had to ask for help. I asked my parents and told my dad everything—that I wasn’t functioning and that I couldn’t handle it. He put me in touch with a friend of his who was a psychiatrist who gave me “hold-over” therapy. She talked and gathered information about how I’d been feeling, and then through her I was put in touch with people who were in Montréal. I got a psychiatrist and I got an official diagnosis as bipolar II and was started on mood stabilizers and things got better. I had to move out of the village, because it was too easy to party all the time and never sleep. I moved to NDG and became a hermit and started doing yoga all the time and got my shit together—but I got my shit together in a way where my house is still messy all the time, and I miss appointments constantly and I’m still a bit ridiculous but I have my shit together."

"If people just let me be a mess, I’m fine. That’s kind of the thing. As long as I’m not feeling a lot of pressure to not be such a mess, in my functional, happy-messy way, I can have my comfy mess and be okay. I have my cluttered apartment, my piles of laundry on the floor, the dishes I haven’t done from the elaborate meal I cooked the night before, I can just take the drugs I’m supposed to take when I’m supposed to take them and drink some wine some times, if I can just be a mess—even if that means showing up to work with messy hair and having forgotten a few thing—as long as that’s okay, I don’t spin out of control and I don’t feel the need to indulge in those manic behaviours. Even on the mood stabilizers if I commit to hypo-mania I can still make it happen, I know myself well enough that I know how to trigger it. Having a relationship with myself and being able to talk myself down keeps me functional and okay."

tenor. you’re using that word incorrectly. it doesn’t mean

what you think it means. it doesn’t mean the heart

of what you think it means. it doesn’t mean

shit. you’re using that word incorrectly.you hear: you’re using that word incorrectly. you’re opening your mouth to

to speak

at all

"I'm using words incorrectly"

Four years, a year, four months

Tara McGowan-Ross: "The reason why I wanted to publish Girth now was that I needed to prove to myself that I could do it. In a bunch of ways, in a bunch of areas of my life, it was really important for me to do it and be proud of it. And I like Girth. I sincerely do! I’m not looking back at the book and thinking: “Oh what a foolish mistake I’ve made! Oh no these are terrible!” I do that with a lot of my work, actually. I guess the book didn’t get published that long ago so ask me again in two years. But a lot of the time, at school, I would look back at the work of the previous semesters and go: “Oh my god. I wrote that and let other people read it?” and I don’t feel that way about this book. I don’t feel like there are any half-baked ideas or ideas that I didn’t execute the way that I wanted to. I’m quite happy with the way it turned out. So having a book that I’m proud of and being able to show it to people who can say: “This is fine.”—Actually, I’m waiting for a bad review. I want someone to hate it so badly! Because then it’s real! Now people just tell me what I want to hear, that it’s amazing or whatever else they think I want to hear, but I just want people to tell me all the problems they have with it or what’s wrong with it!"

"You get that a lot in creative writing workshops but I haven’t gotten any negative feedback yet about my book. Obviously the readership is not enormously wide, it’s not like I wrote Harry Potter where every one is just like: “I’m going to pick apart all your problems now!” But people are just so proud of me for writing this book that they haven’t criticized it. But I live for the bitchyness that comes out during the creative writing workshops. I love it. I got really good at managing it because sometimes it hurts and it sucks especially when it’s true, when someone catches your failures, when you knew that problem was there and you didn’t want people to notice. But also, it made me so good, at least with my writing, at recognizing why I do the things that I do, and why I should feel really confident when people say: “This is really like this, or this is really vague, or whatever, there are too many different interpretations of this!” and I’m like: “Clearly I meant it that way! It’s clearly EXACTLY what I wanted!” It made me realise the importance of knowing why I write the way that I write. The stuff that made it out of the workshops was my strongest stuff, the stuff that not only had positive feedback but had negative feedback that I could refute easily. It wasn’t everybody’s cup of tea, but the reasons some people didn’t like it were actually the reasons that I liked it!"

"I can hear Sina Queyras’ voice in my head—as I always do, I took one class with her and now I’m stuck hearing her voice in my head for the rest of my life—she would always say: “You shouldn’t release any book that you haven’t been writing for at least ten years.” That is her thing about your first book, that you should have been writing it for ten years. I feel like I’ve been writing poetry pretty seriously since I was about fourteen. I’ve been writing in general for about ten years: fiction, and speculative non-fiction in that sort of ridiculous early-teenager kind of way, and also fanfiction. I’ve been writing that stuff since I was about nine or ten. But I’ve been writing poetry since I was about fourteen. So I’ve been developing a voice since about that long. I took it really seriously. The first poem I ever really wrote and put a lot of effort into and really polished off, I read it at a talent show at my school, and that turned into me performing it for my school’s slam team, and then we went on a trip somewhere and we won a slam competition. I took it really seriously and I loved slam poetry and spoken word. But the poems that eventually became Girth—there’s really nothing in there that hasn’t been germinating in some form since I started at Concordia and started taking poetry classes. There’s stuff in there from the class with Stephanie Bolster that we took together. There are poems that have been toyed a little bit, but have been more or less in the same form for that long."

"I had the idea for a collection of poems my last full year at Concordia. During the first semester of that year I handed in a collection of poetry for critique called “Strike Suite”. In it there was “Coke Sex for Teen Sluts” and it had “STRIKE MOTION” and a couple of other things, and that’s when I fleshed out this basic narrative arc of a story. Once I got offered the book deal, after someone heard me read and asked me if I had a pitch for a book, I took “Strike Suite” and made it into a pitch. I submitted, with my pitch, the basic skeleton of the book, which was about ten poems long, everything else that is in the book I wrote after. It was a chapbook or a collection when I was first offered the contract with Insomniac. I wrote a lot of it in the four months after accepting that contract."

"I spent most of those months tree planting and the rest of it in Trois Pistoles. I was outside of Montréal while I wrote the majority of Girth. During my days off treeplanting, sitting and looking like a trashbag, covered in dirt and scratches, typing on my iPhone. I wrote a bunch of it on the phone, and a bunch of it in paper and pen in filthy notebooks covered in crap because I’d taken them to the block to plant trees. Because tree planting is great for writing! I can’t believe how much of my writing process is tree planting. I’m not going tree planting this summer and I don’t know how my writing process is going to survive. You basically spend two months in a field by yourself, thinking. You’re doing repetitive motions and you can completely zone out—I would just drill lines repeatedly in my head, sometimes for ten hours! And then I’d go back to my tent at night and write a poem."

"It kind of took four years, and kind of a year, and kind of four months—that’s how long it took to write Girth."

- I hate the free vegan soup kitchen

because everyone I have ever slept with goes there

and my time is valuable (fuck that line)

and I hate carrying empty tupperware

and I’m always hungry an hour later.

"running list of my failures as a quebec spring student insurrectionist™"

Taking up space

Tara McGowan-Ross: "One way that I have sort of described Girth is that it’s a fictional memoir. It’s fiction—it didn’t happen at all. It’s from the perspective of someone who went through something that actually did happen. I’ve been thinking about it almost like historical poetry, poetry about a particular time and place, and about what happened there. It’s specifically about the printemps 2015 student strike that happened at Concordia in 2015. It was supposed to be a resurgence of the 2012 student strike but it didn’t last nearly as long. It was sort of a structural disaster. Girth is about this speaker who is in her mid-university depressive slump and feels like doesn’t know what she wants to do with her life and feels like everything is out of control for her, and this opportunity to participate in this political action that she actually believes in comes along."

"What’s happening in the poem, and what’s really being said are different. What’s happening in the poem is a student strike. What’s really being said is an eating disorder. The speaker is an overweight person with an eating disorder, which is a special kind of hell. All eating disorders are horrific, obviously, and people who are underweight and have eating disorders suffer in a way that this speaker, and anyone who relates to this speaker, could not possibly understand. But I think, in the same way, people who are overweight and struggle with an eating disorder, they struggle in a way that people who are underweight don’t get. They’re overlooked—technically you can’t be anorexic unless you’re underweight according to the official diagnostic guidelines. So the speaker is overweight and has a serious eating disorder, and has for a long time. It’s a binge, purge, restrict type disorder, they’re a bulimic… I have had the idea for Girth as a title for a book about eating disorders since I was about fourteen-fifteen…"

"I guess I have been writing the book for ten years."

"I wanted to write a book about eating disorders because—and this is another one of those things where “It’s a memoir” is also “It’s totally fake!”—I first got diagnosed with bulimia when I was fifteen. I’d been bulimic for a year and finally told my parents and went to therapy and got an official diagnosis. The poems are all very bodied—they’re very self-conscious poems, in the way that all people with eating disorders are really very aware of how much space they are taking up. Taking up space is a theme throughout the book, as well. Everyone is taking up space as political protesters. And the speaker is also very concerned about her weight, and how she is being viewed by other people."

"The phenomenology of a bulimic eating disorder, or a restrictive-type eating disorder, and also probably bipolar disorder—and also with this particular speaker’s take on resistance—is that it’s so cyclical. There are moments where you totally believe in yourself. And then there are moments where it gets really hard and you just doubt yourself like crazy. For me, as someone who is overweight and has had an eating disorder, there are always these cycles where I say: “No, I am TOTALLY okay with myself! I’m totally confident, and I love myself just the way that I am!” Then, it turns into: “I love myself just the way that I am but I could be better in these ways, and the only way I’ll be better in these ways is if I commit myself really hard to changing.” And it ends up at: “No, I hate myself, and I hate everything about myself.” That flipping back and forth is constant."

"For bulimia and a lot of things that have to do with impulse control, there’s always that moment of “Fuck it! I’m just going to binge.” Or there’s: “Fuck it! I’m just going to purge!” Those two things are constantly at war—there’s trying to resist, and then just going for it. It comes in cycles. You deal with that over and over again. The same thing happens, over and over again, and it still surprises you every single time."

"There’s also realizing you’ve committed to doing something, and it really scares you, because you’re in the moment and you can’t take it back. It's nerve-wracking. The speaker of Girth deals with that a lot when it comes to her political resistance. There are moments when she totally believes in herself and it's super awesome, and then a lot of moment where she feels completely that what she is doing is ridiculous. She feels completely inept, and that no one that she’s with has any idea of what’s going on or what they’re trying to do. She also has moments of real despair because she feels like she can’t do these things—there’s something wrong with her and she can’t access this higher level of confidence and really committing to resistance. When it comes to her habits and her relationship with her body, she feels the same thing."

become accustomed to cycles

learn the names for them later.

your stretch marks will reopen, pink

and new. turn paper in all your corners

for the give and take of it.

learn to love it, like a shore

loves the tides, bitter stink and all.

love the way the hunger keeps you

safe from more nights drinking,

how the all of you renders you sure

of your worthlessness, so sure

it will protect you from the way his fingers

scraped your wrists, inviting.

learn to apologize for your body

with a look, or better, learn not to,

I guess. I don’t know. learn something

like, “you are the only one who hasn’t

been loving you.” or, “all bodies are…”

something.

"epistle to myself at twenty

or phenom-nom-nomenology"

Thank you so much, Tara, for taking the time to sit and speak with me. And thank you for writing this book.

I did it

for the babes."running list of my failures as a quebec spring student insurrectionist™"

Buy Girth by Tara McGowan-Ross, Insomniac Press, 2016 by clicking right here so that you can feast your eyeballs on every single on of her poems. You can (and should) also follow Tara on twitter @timehead_.